Buckminster Fuller's Geometric Futures

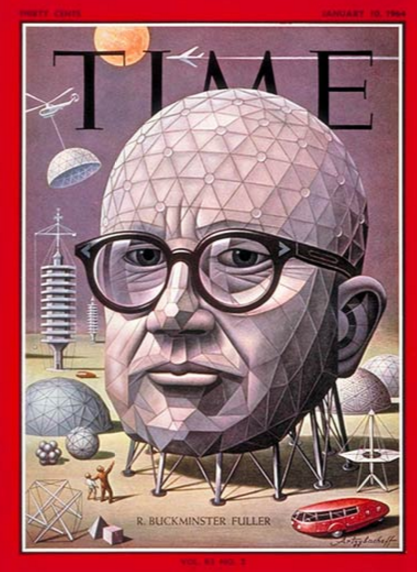

Note: This blog post is adapted from a recent essay - a review of Jonathon Keats’s new book You Belong to the Universe - I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books. Enjoy... There are two possible views of Buckminster Fuller. Consider: “Bucky” to friends and family – Fuller was a true American visionary, a solitary innovator who forged ahead as corporate research and development displaced the lone inventor. A kindly and bespectacled blend of Henry David Thoreau, Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford, Fuller was so far ahead of his time that the future, let alone the present, has caught up to him. From his experimental Dymaxion cars to the geodesic domes that made him an international figure and unlikely counterculture guru, Fuller promoted environmentally conscious designs with the potential to benefit everyone on Spaceship Earth.Or...a consummate bullshit artist, Bucky Fuller’s career was a failure, if not an outright fraud. With few ideas achieving any commercial success, Fuller was a hand-waving proponent of outlandish notions. An aggressive manager of his profile and patents, the authoritarian technocrat sought not students but compliant disciples who would spread Fuller’s muddled messages. Even the geodesic dome, Fuller’s greatest “success,” rested on a concept borrowed, if not stolen, from an aspiring sculptor and student. Even Spaceship Earth was a concept Fuller claimed as his own.The reality is a smeared superposition these two representations, a blend of the visionary’s own mythologizing and the historical record. Peeling away the mythic layers that Fuller and his acolytes applied to his life like so many layers of fertilizer is no easy task. It’s not for a lack of historical sources. Fuller consciously, even obsessively, documented his existence. His “Chronofile” is perhaps the most comprehensive record of any individual’s life. Now owned by Stanford University, it challenges scholars with 1200 linear feet of boxes containing manuscripts, models, design drawings, and audio-visual recordings (as well as overdue library notices and grocery lists). Fuller’s was not a life unrecorded.Peaking through that smokescreen of self-mythologizing is evidence that even when it came to basic, even pivotal, moments in Fuller’s life, the visionary designer was anything but a reliable narrator. Yet this interpretative flexibility with historical facts and professional accomplishments proved central to Fuller’s undeniable success.Consider the accomplishment Fuller is most famed for - the geodesic dome. Geodesics – the domes themselves and their underlying geometry – made Buckminster Fuller into an international celebrity. When Time featured him on its cover in 1964, the now-familiar architecture dominated the picture as it did fifty years later when a U.S. postage stamp (pictured above) honored Fuller.Fuller’s most prominent invention originated not in some military laboratory but in the avant-garde atmosphere of North Carolina’s Black Mountain College in 1948 where he was visiting as an architecture professor. The students tried, with Fuller’s supervision, to build a structure using Venetian blind slats as trusses held in place via tension.

There are two possible views of Buckminster Fuller. Consider: “Bucky” to friends and family – Fuller was a true American visionary, a solitary innovator who forged ahead as corporate research and development displaced the lone inventor. A kindly and bespectacled blend of Henry David Thoreau, Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford, Fuller was so far ahead of his time that the future, let alone the present, has caught up to him. From his experimental Dymaxion cars to the geodesic domes that made him an international figure and unlikely counterculture guru, Fuller promoted environmentally conscious designs with the potential to benefit everyone on Spaceship Earth.Or...a consummate bullshit artist, Bucky Fuller’s career was a failure, if not an outright fraud. With few ideas achieving any commercial success, Fuller was a hand-waving proponent of outlandish notions. An aggressive manager of his profile and patents, the authoritarian technocrat sought not students but compliant disciples who would spread Fuller’s muddled messages. Even the geodesic dome, Fuller’s greatest “success,” rested on a concept borrowed, if not stolen, from an aspiring sculptor and student. Even Spaceship Earth was a concept Fuller claimed as his own.The reality is a smeared superposition these two representations, a blend of the visionary’s own mythologizing and the historical record. Peeling away the mythic layers that Fuller and his acolytes applied to his life like so many layers of fertilizer is no easy task. It’s not for a lack of historical sources. Fuller consciously, even obsessively, documented his existence. His “Chronofile” is perhaps the most comprehensive record of any individual’s life. Now owned by Stanford University, it challenges scholars with 1200 linear feet of boxes containing manuscripts, models, design drawings, and audio-visual recordings (as well as overdue library notices and grocery lists). Fuller’s was not a life unrecorded.Peaking through that smokescreen of self-mythologizing is evidence that even when it came to basic, even pivotal, moments in Fuller’s life, the visionary designer was anything but a reliable narrator. Yet this interpretative flexibility with historical facts and professional accomplishments proved central to Fuller’s undeniable success.Consider the accomplishment Fuller is most famed for - the geodesic dome. Geodesics – the domes themselves and their underlying geometry – made Buckminster Fuller into an international celebrity. When Time featured him on its cover in 1964, the now-familiar architecture dominated the picture as it did fifty years later when a U.S. postage stamp (pictured above) honored Fuller.Fuller’s most prominent invention originated not in some military laboratory but in the avant-garde atmosphere of North Carolina’s Black Mountain College in 1948 where he was visiting as an architecture professor. The students tried, with Fuller’s supervision, to build a structure using Venetian blind slats as trusses held in place via tension.

It collapsed.

One of the students affected by Fuller’s Dymaxion ideas, however, was a young art student named Kenneth Snelson. Over the winter of 1948-49, he built a series of models in which the parts were held in place by taut wires, their balance of compression and tension providing structural stability. After returning to Black Mountain College, Snelson showed Fuller his model. By the end of the summer of 1949, the school’s art students, guided by Fuller, successfully built a geodesic dome using aluminum tubes.

One of the students affected by Fuller’s Dymaxion ideas, however, was a young art student named Kenneth Snelson. Over the winter of 1948-49, he built a series of models in which the parts were held in place by taut wires, their balance of compression and tension providing structural stability. After returning to Black Mountain College, Snelson showed Fuller his model. By the end of the summer of 1949, the school’s art students, guided by Fuller, successfully built a geodesic dome using aluminum tubes. Its basic principle is evident via its structure. Geodesic domes feature a superstructure of complex polyhedra based on interconnected triangles. Their advantage comes from their strength-to-weight ratio and relative ease of transport and assembly.Fuller began to refer to the engineering principle Snelson had used as “tensegrity” – a clever portmanteau of “tension” and “integrity” – that he later patented just as he did with the geodesic dome. Snelson’s name was in neither patent application. The stage was set for a priority dispute between Snelson and Fuller that lasted decades. (Snelson's version of the story is presented here...)Fuller’s intellectual property claims notwithstanding, the artist went on to have a successful career as sculptor. Snelson’s “Needle Tower, a 60-foot tall “tensegrity” piece sits in front of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington.

Its basic principle is evident via its structure. Geodesic domes feature a superstructure of complex polyhedra based on interconnected triangles. Their advantage comes from their strength-to-weight ratio and relative ease of transport and assembly.Fuller began to refer to the engineering principle Snelson had used as “tensegrity” – a clever portmanteau of “tension” and “integrity” – that he later patented just as he did with the geodesic dome. Snelson’s name was in neither patent application. The stage was set for a priority dispute between Snelson and Fuller that lasted decades. (Snelson's version of the story is presented here...)Fuller’s intellectual property claims notwithstanding, the artist went on to have a successful career as sculptor. Snelson’s “Needle Tower, a 60-foot tall “tensegrity” piece sits in front of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington. In historical research, sorting out “who discovered it first” claims is a tricky and often unenlightening business. The past is littered with examples of simultaneous invention. In this case, the truth likely lies between Fuller’s opportunism and Snelson’s protestations. Developing and promoting the geodesic dome – inventing something isn’t the same as nurturing its diffusion – certainly required some synergy between teacher and student.Promoting the geodesic dome’s potential was something Fuller, the consummate booster-cum-huckster, excelled at. Starting in 1949, Fuller the technocrat pushed geodesic domes as a key tool for American success on the Cold War battlefield both on the frontlines and at home. That same year, he oversaw a demonstration dome’s construction at the Pentagon and worked with MIT students to design another one that could shelter Air Force planes and their crews. The Marine Corps eventually had 300 of them built, envisioning their speedy deployment into combat hot zones.

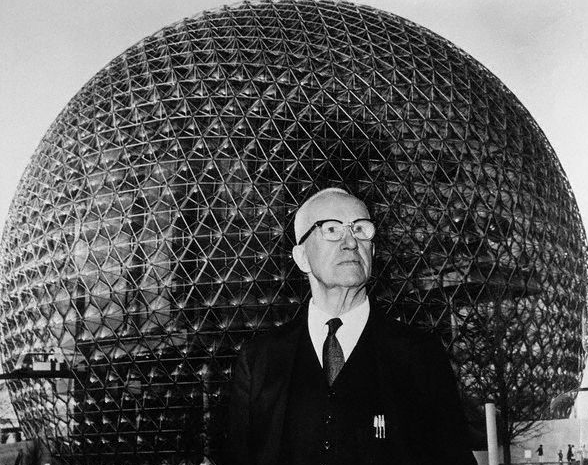

In historical research, sorting out “who discovered it first” claims is a tricky and often unenlightening business. The past is littered with examples of simultaneous invention. In this case, the truth likely lies between Fuller’s opportunism and Snelson’s protestations. Developing and promoting the geodesic dome – inventing something isn’t the same as nurturing its diffusion – certainly required some synergy between teacher and student.Promoting the geodesic dome’s potential was something Fuller, the consummate booster-cum-huckster, excelled at. Starting in 1949, Fuller the technocrat pushed geodesic domes as a key tool for American success on the Cold War battlefield both on the frontlines and at home. That same year, he oversaw a demonstration dome’s construction at the Pentagon and worked with MIT students to design another one that could shelter Air Force planes and their crews. The Marine Corps eventually had 300 of them built, envisioning their speedy deployment into combat hot zones. Fuller originally set up companies to make his domes but, starting in 1966, he licensed, for a 5% royalty, scores of other companies to make them. As they migrated from military bases to trade fairs, geodesic domes became not just a product of American capitalism but a symbol of it as well. At the 1967 World's Fair, Fuller's dome was the featured design for the U.S. pavilion.

Fuller originally set up companies to make his domes but, starting in 1966, he licensed, for a 5% royalty, scores of other companies to make them. As they migrated from military bases to trade fairs, geodesic domes became not just a product of American capitalism but a symbol of it as well. At the 1967 World's Fair, Fuller's dome was the featured design for the U.S. pavilion. The dome’s final, wonderfully ironic, transmutation occurred at the hands of America’s counterculture. At places like Drop City, a Colorado hippie commune started in 1965, geodesic domes popped up like so many mushrooms.

The dome’s final, wonderfully ironic, transmutation occurred at the hands of America’s counterculture. At places like Drop City, a Colorado hippie commune started in 1965, geodesic domes popped up like so many mushrooms. And, like so many aspects of that groovy era, geodesic domes – promoted by venues such as The Whole Earth Catalog – were marketed and sold. For example, Californian Lloyd Kahn converted to Fuller-ism after hearing him speak at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. “Enthralled by Fuller’s idea that waste could be eliminated by design,” Kahn produced books extolling domes as homes before renouncing them as a universal panacea for the world’s housing shortages and environmental problems.Over three decade’s Fuller’s architectural icon had traveled from art project to Cold War instrument of power to countercultural icon to a fading symbol of utopian aspirations. What a long strange trip it had been.

And, like so many aspects of that groovy era, geodesic domes – promoted by venues such as The Whole Earth Catalog – were marketed and sold. For example, Californian Lloyd Kahn converted to Fuller-ism after hearing him speak at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. “Enthralled by Fuller’s idea that waste could be eliminated by design,” Kahn produced books extolling domes as homes before renouncing them as a universal panacea for the world’s housing shortages and environmental problems.Over three decade’s Fuller’s architectural icon had traveled from art project to Cold War instrument of power to countercultural icon to a fading symbol of utopian aspirations. What a long strange trip it had been.