Remembering Lines of Light

Two years ago, the UN General Assembly declared 2015 as the International Year of Light. This “global initiative” is to highlight the “importance of light and optical technologies” in the lives of the world’s citizens. Which technologies? Consider the laser. I’ll bet there’s one within 30 feet of you – in a CD player, a computer mouse, a checkout scanner. Maybe you’re using one to amuse your cat.Invented – perhaps more than once – in the late 1950s, a decade later lasers were still a novelty. Many people, at least those who were not physicists, probably saw one for the first time when James Bond was almost bifurcated by a laser beam in Goldfinger (1964). An advertisement in an industry journal a few years before Ian Fleming’s novel became a blockbuster film asked the question: “Where does the laser go from here?” One of the places it went was the artist’s studio and the art gallery.

An advertisement in an industry journal a few years before Ian Fleming’s novel became a blockbuster film asked the question: “Where does the laser go from here?” One of the places it went was the artist’s studio and the art gallery. The laser’s light – pure, bright, and steady – captivated a small group of artists who began to explore its aesthetic potential. This wasn’t easy to do. In the mid-1960s, lasers were delicate pieces of equipment, often requiring one or even several experts to make them work properly. They were also expensive – a small commercial unit could cost as much as $700 (about $5500 in today’s money).Given the cost and complexity, getting access to and then being able to work with a laser was not always easy for artists. Carl Frederik Reuterswärd, a Swedish artist, recalled learning about the laser just a few years after it was invented. But it wasn’t until 1965, when fellow Swede Billy Klüver, an engineer and co-founder of the seminal group Experiments in Art and Technology, brought him to Bell Labs to show him one in action. The artist recalled, “My mental perceptions changed. Here was the tool that broke with all traditions…It looked like the halo of Leonardo da Vinci, but straightened to infinity.”Even more debatable than which scientist invented the laser – the story is complicated and, unless one has a commercial stake, it’s not a particularly interesting historical question – is which artist first used lasers for art’s sake. During the short-lived but remarkably fecund Art & Technology Movement of the mid-to-late 1960s, many such experiments were done. Some were done by physicists – like Caltech’s Elsa Garmire – who wanted to expand their careers in new directions. Other efforts were made by artists wanting to explore a new medium.While many people experimented with the aesthetic possibilities of lasers, far fewer persisted with it as their preferred medium. One possible reason might be the ways in which lasers were incorporated into light shows and rock concerts – high art of a very different nature. Remember Laserium?One artist who started experimenting early with lasers and maintained this focus for many years to follow was Rockne Krebs. Born in Kansas City, Missouri in 1938, Krebs got a B.A. in sculpture from the University of Kansas in 1961. After a stint in the Navy, Krebs settled in Washington, DC and started his art career in earnest. Photos of him early in his career show him with his hair still cut in near-Navy fashion.

The laser’s light – pure, bright, and steady – captivated a small group of artists who began to explore its aesthetic potential. This wasn’t easy to do. In the mid-1960s, lasers were delicate pieces of equipment, often requiring one or even several experts to make them work properly. They were also expensive – a small commercial unit could cost as much as $700 (about $5500 in today’s money).Given the cost and complexity, getting access to and then being able to work with a laser was not always easy for artists. Carl Frederik Reuterswärd, a Swedish artist, recalled learning about the laser just a few years after it was invented. But it wasn’t until 1965, when fellow Swede Billy Klüver, an engineer and co-founder of the seminal group Experiments in Art and Technology, brought him to Bell Labs to show him one in action. The artist recalled, “My mental perceptions changed. Here was the tool that broke with all traditions…It looked like the halo of Leonardo da Vinci, but straightened to infinity.”Even more debatable than which scientist invented the laser – the story is complicated and, unless one has a commercial stake, it’s not a particularly interesting historical question – is which artist first used lasers for art’s sake. During the short-lived but remarkably fecund Art & Technology Movement of the mid-to-late 1960s, many such experiments were done. Some were done by physicists – like Caltech’s Elsa Garmire – who wanted to expand their careers in new directions. Other efforts were made by artists wanting to explore a new medium.While many people experimented with the aesthetic possibilities of lasers, far fewer persisted with it as their preferred medium. One possible reason might be the ways in which lasers were incorporated into light shows and rock concerts – high art of a very different nature. Remember Laserium?One artist who started experimenting early with lasers and maintained this focus for many years to follow was Rockne Krebs. Born in Kansas City, Missouri in 1938, Krebs got a B.A. in sculpture from the University of Kansas in 1961. After a stint in the Navy, Krebs settled in Washington, DC and started his art career in earnest. Photos of him early in his career show him with his hair still cut in near-Navy fashion. By the end of the 1960s, Krebs looked less like a Navy officer and more like a slightly heftier Robert Redford. As carefully planned and executed as his art works were, the ruggedly handsome Krebs – ubiquitous cigarette in hand – cut a path in his personal life somewhat less straight than a laser beam.

By the end of the 1960s, Krebs looked less like a Navy officer and more like a slightly heftier Robert Redford. As carefully planned and executed as his art works were, the ruggedly handsome Krebs – ubiquitous cigarette in hand – cut a path in his personal life somewhat less straight than a laser beam. Krebs started making his early works from more traditional materials – a show in January 1967 at the Jefferson Place Gallery in Washington, DC featured pieces of Plexiglas, aluminum and steel that the Washington Post called “starkly courageous.”By spring of 1967, though, Krebs had begun to shift to the ephemeral medium of laser light. At first he experimented at home with a laser he had “panhandled.” Then, at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Paul Haldemann, a technician from the University of Maryland’s electrical engineering department, assisted Krebs in combining red laser beams with artificial fog and mirrors. As he later said, Krebs was prompted by “the possibility of reversing the proposition by which we normally view sculpture.” The result was best explained by the show’s name - Sculpture Minus Object.

Krebs started making his early works from more traditional materials – a show in January 1967 at the Jefferson Place Gallery in Washington, DC featured pieces of Plexiglas, aluminum and steel that the Washington Post called “starkly courageous.”By spring of 1967, though, Krebs had begun to shift to the ephemeral medium of laser light. At first he experimented at home with a laser he had “panhandled.” Then, at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Paul Haldemann, a technician from the University of Maryland’s electrical engineering department, assisted Krebs in combining red laser beams with artificial fog and mirrors. As he later said, Krebs was prompted by “the possibility of reversing the proposition by which we normally view sculpture.” The result was best explained by the show’s name - Sculpture Minus Object. Along with Sam Gilliam, his longtime friend with whom he shared a studio, Krebs secured a growing reputation for his works which used lasers and other light sources in innovative if dematerialized ways.

Along with Sam Gilliam, his longtime friend with whom he shared a studio, Krebs secured a growing reputation for his works which used lasers and other light sources in innovative if dematerialized ways. This was enhanced considerably when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) selected Krebs as part of its controversial Art and Technology Program. Conceived in 1966 by LACMA curator Maurice Tuchman, the idea of A&T was to pair artists with various companies, primarily based in southern California. Working in collaboration with company engineers and supported by modest stipends from the corporate pay chest, artists would create pieces for an eventual show at LACMA.Most of the participating artists were big names in the New York avant-garde art world – Warhol, Oldenburg, Serra, Rauschenberg. Krebs, barely 30 years old and from Washington, DC (hardly seen at the vanguard of the 1960s art scene) was a relative outsider. Nonetheless, in March 1969, prodded by “gonzo curator” Walter Hopps, a recent transplant from Los Angeles to DC, Krebs wrote LACMA to express interest in the A&T effort. He proposed making two works of art, one to be set up outdoors and shown at night and another to be installed indoors.One of the companies Tuchman had approached about being partners in the A&T Program was Hewlett-Packard, a long-established Bay Area firm. Krebs flew out to California and met with Hewlett-Packard engineers and managers. Krebs was especially interested in H-P because, after “several years of ideation and attempts to visualize pieces that were beyond my resources,” H-P could offer both technical skills and the money for him to pursue more ambitious works.Krebs began to collaborate with Larry Hubby, a physicist at H-P, who helped him resolve issues with the power output of lasers, light scattering, and how to focus the laser light. (Authorial aside: If any readers have contact information for Mr. Hubby, please write me!) Hewlett-Packard featured the artist-engineer collaboration in its magazine, highlighting technical input the company was providing. Here, we can still see shades of the famous "two cultures" divide. According to the H-P writer, Krebs, although "attired...in the informal style conventional to artists" still managed to impress H-P employees as "serious, talented, and pleasant to work with." One of the engineers' main contributions was developing a complex beam-switching sequence as Krebs wanted to use green and blue light from an argon laser as well as red light from a helium-neon laser.

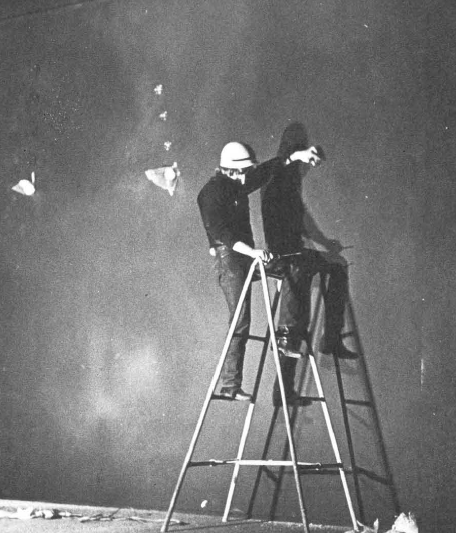

This was enhanced considerably when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) selected Krebs as part of its controversial Art and Technology Program. Conceived in 1966 by LACMA curator Maurice Tuchman, the idea of A&T was to pair artists with various companies, primarily based in southern California. Working in collaboration with company engineers and supported by modest stipends from the corporate pay chest, artists would create pieces for an eventual show at LACMA.Most of the participating artists were big names in the New York avant-garde art world – Warhol, Oldenburg, Serra, Rauschenberg. Krebs, barely 30 years old and from Washington, DC (hardly seen at the vanguard of the 1960s art scene) was a relative outsider. Nonetheless, in March 1969, prodded by “gonzo curator” Walter Hopps, a recent transplant from Los Angeles to DC, Krebs wrote LACMA to express interest in the A&T effort. He proposed making two works of art, one to be set up outdoors and shown at night and another to be installed indoors.One of the companies Tuchman had approached about being partners in the A&T Program was Hewlett-Packard, a long-established Bay Area firm. Krebs flew out to California and met with Hewlett-Packard engineers and managers. Krebs was especially interested in H-P because, after “several years of ideation and attempts to visualize pieces that were beyond my resources,” H-P could offer both technical skills and the money for him to pursue more ambitious works.Krebs began to collaborate with Larry Hubby, a physicist at H-P, who helped him resolve issues with the power output of lasers, light scattering, and how to focus the laser light. (Authorial aside: If any readers have contact information for Mr. Hubby, please write me!) Hewlett-Packard featured the artist-engineer collaboration in its magazine, highlighting technical input the company was providing. Here, we can still see shades of the famous "two cultures" divide. According to the H-P writer, Krebs, although "attired...in the informal style conventional to artists" still managed to impress H-P employees as "serious, talented, and pleasant to work with." One of the engineers' main contributions was developing a complex beam-switching sequence as Krebs wanted to use green and blue light from an argon laser as well as red light from a helium-neon laser. Meanwhile, LACMA’s Tuchman negotiated with Jack Masey the United States Information Agency to put a selection of works by artists involved with the A&T Program in the official pavilion the U.S. would have at the Osaka ’70 Expo. Krebs was one of eight American artists invited to bring their collaborative art work to Japan where it would be displayed alongside sports memorabilia, and moon rocks brought back by Apollo 12 astronauts.In January 1970, Krebs flew to Osaka for a 6-week stay. Working mostly alone at night, he installed the delicate and complex electro-optical system that would generate his light sculpture.

Meanwhile, LACMA’s Tuchman negotiated with Jack Masey the United States Information Agency to put a selection of works by artists involved with the A&T Program in the official pavilion the U.S. would have at the Osaka ’70 Expo. Krebs was one of eight American artists invited to bring their collaborative art work to Japan where it would be displayed alongside sports memorabilia, and moon rocks brought back by Apollo 12 astronauts.In January 1970, Krebs flew to Osaka for a 6-week stay. Working mostly alone at night, he installed the delicate and complex electro-optical system that would generate his light sculpture. It included three argon beams that would flash off and on, changing color at times throughout a seven minute cycle. In addition, red laser light formed a “static beam network” providing a sculptural armature.

It included three argon beams that would flash off and on, changing color at times throughout a seven minute cycle. In addition, red laser light formed a “static beam network” providing a sculptural armature. The technical help that H-P engineers provided was critical to success of the piece. As Krebs told The Washington Post, “They’d build the things I dreamed.” His artistic vision was to “weaken the psychological persistence with which laser beams are perceived as apparently real matter.” He wanted to do this by having the beams appear and disappear in different configurations to “convey both the transiency and relativeness” of the piece the Los Angeles Times called “Infinity Reflection System”.Still photos can’t convey the visual effect of seeing Krebs’ piece in person. Remember that for many visitors to Expo ’70, this was the first time they had ever seen a laser in person. Unlike Krebs’ earlier static works, his Osaka creation changed over time. One reviewer wrote that the viewer “is confronted with a red wall of light above the floor which forms a nonphysical curtain through which he passes."

The technical help that H-P engineers provided was critical to success of the piece. As Krebs told The Washington Post, “They’d build the things I dreamed.” His artistic vision was to “weaken the psychological persistence with which laser beams are perceived as apparently real matter.” He wanted to do this by having the beams appear and disappear in different configurations to “convey both the transiency and relativeness” of the piece the Los Angeles Times called “Infinity Reflection System”.Still photos can’t convey the visual effect of seeing Krebs’ piece in person. Remember that for many visitors to Expo ’70, this was the first time they had ever seen a laser in person. Unlike Krebs’ earlier static works, his Osaka creation changed over time. One reviewer wrote that the viewer “is confronted with a red wall of light above the floor which forms a nonphysical curtain through which he passes." As one entered the "periphery of the large mirrors used in this experiment, the walls appear to open as the mirrors reflect a laser beam structure that can be seen in real space.” ((Harry J. Seldis, “The Art of Tomorrow,” Los Angeles Times, 7 June 1970)) The effect was to generate structures and walls of light which changed color – “green…and then without warning, nose or movement…the brightest sort of blue” – and winked into existence and then away. Krebs designed the piece so that pace would gradually increase, creating a “kind of silent visual crescendo.”Critics’ reaction to the high-tech art on display in Osaka – it was a big theme that year with the Pepsi Pavilion built by Experiments in Art and Technology standing out as the most ambitious attempt to marry art and engineering – was mixed. Krebs’ work received a positive response. Perhaps not surprisingly, a critic from Krebs’ hometown was especially positive, calling him the “most important innovative sculptor” that Washington DC had ever produced.The Osaka Expo and, a year later, LACMA's Art and Technology (which featured another ambitious laser installation) brought Krebs national attention and prestigious commissions. Before his death in 2011, Krebs designed and built more than 30 large-scale public art works which all involved light, optical effects, and, often, lasers. In addition, he exhibited in dozens of solo and group shows.

As one entered the "periphery of the large mirrors used in this experiment, the walls appear to open as the mirrors reflect a laser beam structure that can be seen in real space.” ((Harry J. Seldis, “The Art of Tomorrow,” Los Angeles Times, 7 June 1970)) The effect was to generate structures and walls of light which changed color – “green…and then without warning, nose or movement…the brightest sort of blue” – and winked into existence and then away. Krebs designed the piece so that pace would gradually increase, creating a “kind of silent visual crescendo.”Critics’ reaction to the high-tech art on display in Osaka – it was a big theme that year with the Pepsi Pavilion built by Experiments in Art and Technology standing out as the most ambitious attempt to marry art and engineering – was mixed. Krebs’ work received a positive response. Perhaps not surprisingly, a critic from Krebs’ hometown was especially positive, calling him the “most important innovative sculptor” that Washington DC had ever produced.The Osaka Expo and, a year later, LACMA's Art and Technology (which featured another ambitious laser installation) brought Krebs national attention and prestigious commissions. Before his death in 2011, Krebs designed and built more than 30 large-scale public art works which all involved light, optical effects, and, often, lasers. In addition, he exhibited in dozens of solo and group shows. Krebs' public works were generally without overt political messages. However, in 1988, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, responding to political pressure, canceled an exhibition of artworks by photographer Robert Mapplethorpe who had recently died of AIDS. Krebs - implementing an idea curator Andrea Pollan proposed - sent a light-based “fuck you” to censors and prudes by projecting haunting images of Mapplethorpe and his works on the building’s façade.

Krebs' public works were generally without overt political messages. However, in 1988, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, responding to political pressure, canceled an exhibition of artworks by photographer Robert Mapplethorpe who had recently died of AIDS. Krebs - implementing an idea curator Andrea Pollan proposed - sent a light-based “fuck you” to censors and prudes by projecting haunting images of Mapplethorpe and his works on the building’s façade. Although millions of people saw Krebs' work during his lifetime, the realizations of his artistic vision were necessarily ephemeral. When the electricity is turned off and the laser light disappears, what – besides an impressive volume of sketches, drawings, and diagrams – is left? Memories and impressions.

Although millions of people saw Krebs' work during his lifetime, the realizations of his artistic vision were necessarily ephemeral. When the electricity is turned off and the laser light disappears, what – besides an impressive volume of sketches, drawings, and diagrams – is left? Memories and impressions.