Frank Malina's Cosmos

Frank J. Malina had three careers. His first, the one he is best known for – but not nearly well enough – was as an aeronautical engineer. Although Wernher von Braun received the press attention and Time magazine covers, it was the American-born Malina who researched and developed the U.S.'s first space-capable rockets. ((MG Lord's excellent book Astro Turf discusses the historical injustice of a former Nazi getting the attention while U.S.-born Malina's accomplishments were sidelined during the McCarthy era.)) Jules Verne’s classic book De la Terre à la Lune inspired Malina to think seriously about space exploration. He read the book in Czech when his family relocated from Texas back to Europe when he was a young teen. After returning to the U.S., he attended Texas A&M as an undergraduate – he paid for his tuition, in part, by bugling reveille to the student body – before a graduate fellowship brought him to Caltech in 1934. He stayed in Pasadena for 13 years, designing and building rockets and the motors that propelled them. Then project started small - the original team is shown below - but, driven by wartime concerns, expanded quickly into a multi-million dollar effort employing scores of people.

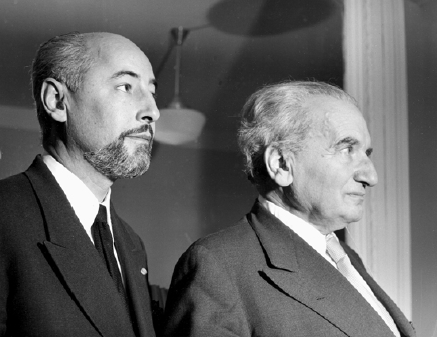

Jules Verne’s classic book De la Terre à la Lune inspired Malina to think seriously about space exploration. He read the book in Czech when his family relocated from Texas back to Europe when he was a young teen. After returning to the U.S., he attended Texas A&M as an undergraduate – he paid for his tuition, in part, by bugling reveille to the student body – before a graduate fellowship brought him to Caltech in 1934. He stayed in Pasadena for 13 years, designing and building rockets and the motors that propelled them. Then project started small - the original team is shown below - but, driven by wartime concerns, expanded quickly into a multi-million dollar effort employing scores of people. While based at Caltech, Malina worked under the tutelage of Hungarian-born research engineer Theodore von Kármán who became his close friend and business partner – the two of them helped start a soon-to-be-very-profitable company called Aerojet. The two engineers also started the Jet Propulsion Laboratory with Malina serving briefly as the lab’s first director.

While based at Caltech, Malina worked under the tutelage of Hungarian-born research engineer Theodore von Kármán who became his close friend and business partner – the two of them helped start a soon-to-be-very-profitable company called Aerojet. The two engineers also started the Jet Propulsion Laboratory with Malina serving briefly as the lab’s first director. The apogee of Malina’s rocket career happened at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The site was close to where Robert Goddard had once tested his rockets and, more ominously, only about 70 miles from where the U.S. Army had exploded the Trinity device three months earlier. Malina visited the Trinity site, in fact, soon after the test and the experience sobered him about the potential realities of future wars.

The apogee of Malina’s rocket career happened at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The site was close to where Robert Goddard had once tested his rockets and, more ominously, only about 70 miles from where the U.S. Army had exploded the Trinity device three months earlier. Malina visited the Trinity site, in fact, soon after the test and the experience sobered him about the potential realities of future wars. In October 1945 at White Sands, a yellow and black sounding rocket called the WAC-Corporal roared from a launch pad. ((“WAC” stood for “Without Any Control” or, since it was the “little sister” of the larger Corporal rocket, which followed an earlier rocket named Private, “Women’s Army Corps.”)) Radar tracked it as it soared to about 240,000 feet, escaping the immediate confines of the earth’s atmosphere. ((In the years that follow, JPL advocates sometimes misstated Malina's accomplishment, considerable though it was. While doing research for his excellent book The Rocket and the Reich, historian Michael Neufeld learned that one V-2 launch in 1944 went as high as 109 miles. Even routine V-2 launches at London exceeded 240,000 ft. As he told me in an email: "There is a whole history of exaggerated assertions about the WAC and the Bumper [a combination of a V-2 + WAC Corporal] being the first human objects in space. As to the Bumper claim, this also involves the changing definition of what is space. There was a tendency after the war more often to put it rather high because of the tenuous outer atmosphere. Only over decades did we settle on 100 km as the unofficial but widely accepted number."))Despite technical accomplishments and considerable military interest, the deepening ideological tensions of the Nuclear Age distressed Malina. Ironically, the success of Aerojet, catalyzed by Cold War funding and military demands, would also make him quite wealthy, free, in fact, to pursue other more peaceful paths. In a few short years after 1946, he left Caltech, moved to Paris, got divorced, and remarried. A strong believer in international cooperation, Malina also joined the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), eventually becoming head of its Division of Scientific Research.Malina could not escape the Cold War, however, and its McCarthy-era suspicions. He had colleagues at Caltech with pink, if not red, pasts and his own FBI file was of considerable heft. Government harassment coupled with financial independence prompted him to quit the UNESCO post in 1953 and start a new career as an artist.

In October 1945 at White Sands, a yellow and black sounding rocket called the WAC-Corporal roared from a launch pad. ((“WAC” stood for “Without Any Control” or, since it was the “little sister” of the larger Corporal rocket, which followed an earlier rocket named Private, “Women’s Army Corps.”)) Radar tracked it as it soared to about 240,000 feet, escaping the immediate confines of the earth’s atmosphere. ((In the years that follow, JPL advocates sometimes misstated Malina's accomplishment, considerable though it was. While doing research for his excellent book The Rocket and the Reich, historian Michael Neufeld learned that one V-2 launch in 1944 went as high as 109 miles. Even routine V-2 launches at London exceeded 240,000 ft. As he told me in an email: "There is a whole history of exaggerated assertions about the WAC and the Bumper [a combination of a V-2 + WAC Corporal] being the first human objects in space. As to the Bumper claim, this also involves the changing definition of what is space. There was a tendency after the war more often to put it rather high because of the tenuous outer atmosphere. Only over decades did we settle on 100 km as the unofficial but widely accepted number."))Despite technical accomplishments and considerable military interest, the deepening ideological tensions of the Nuclear Age distressed Malina. Ironically, the success of Aerojet, catalyzed by Cold War funding and military demands, would also make him quite wealthy, free, in fact, to pursue other more peaceful paths. In a few short years after 1946, he left Caltech, moved to Paris, got divorced, and remarried. A strong believer in international cooperation, Malina also joined the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), eventually becoming head of its Division of Scientific Research.Malina could not escape the Cold War, however, and its McCarthy-era suspicions. He had colleagues at Caltech with pink, if not red, pasts and his own FBI file was of considerable heft. Government harassment coupled with financial independence prompted him to quit the UNESCO post in 1953 and start a new career as an artist. In this, Malina resembles another Frank – Frank Oppenheimer. Younger brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Frank O’s encounters with the national hysteria state were much more severe. After losing his post at the University of Minnesota, the younger Oppenheimer wandered the wilderness, literally, before reinventing himself as the founder of the Exploratorium, an innovative art-science institution, in 1968.Malina had long been interested in art – his parents were both professional musicians – and he put himself through school by sometimes doing engineering drawings. Malina started his new career with traditional painting and quickly secured a one-man show at a Paris gallery. Less enthused about painting as a medium, around 1955, he turned his attention to making light-based and kinetic art works. ((A catalog, compiled by Fabrice Lapelletrie, of Malina's artwork is here.))

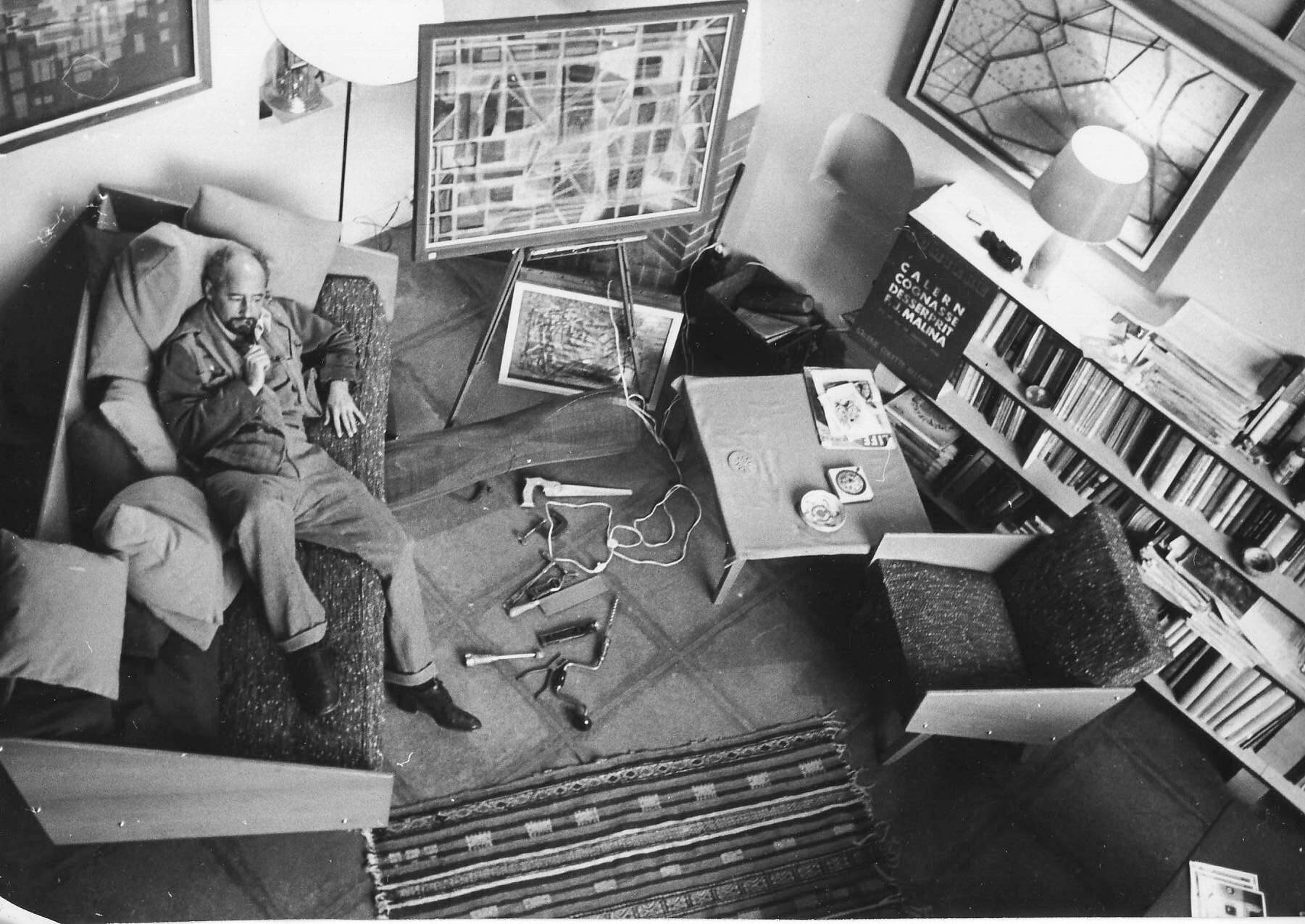

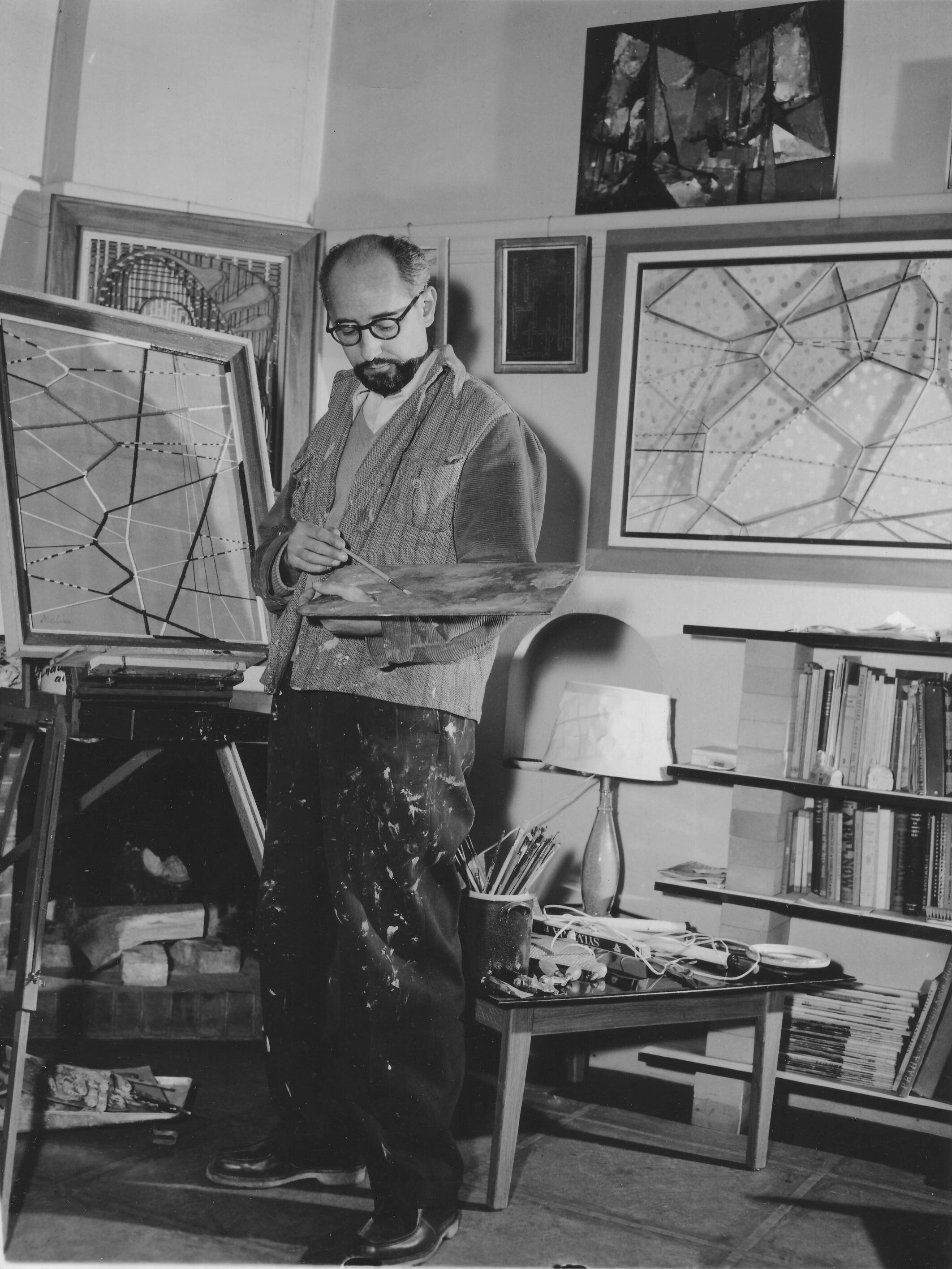

In this, Malina resembles another Frank – Frank Oppenheimer. Younger brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Frank O’s encounters with the national hysteria state were much more severe. After losing his post at the University of Minnesota, the younger Oppenheimer wandered the wilderness, literally, before reinventing himself as the founder of the Exploratorium, an innovative art-science institution, in 1968.Malina had long been interested in art – his parents were both professional musicians – and he put himself through school by sometimes doing engineering drawings. Malina started his new career with traditional painting and quickly secured a one-man show at a Paris gallery. Less enthused about painting as a medium, around 1955, he turned his attention to making light-based and kinetic art works. ((A catalog, compiled by Fabrice Lapelletrie, of Malina's artwork is here.)) Malina was especially keen to introduce material from science and technology, particularly space exploration and astronomy, into contemporary visual arts. Even his early forays into painting incorporated “shock waves and fluid flow and paintings of airplanes and rockets.” As he moved away from traditional art techniques, Malina spent considerable time experimenting with new ways to create novel visual effects. In the mid-1950s, for example, Malina worked with a French electronics student to create what he called his Lumidyne technique. He made his first pieces using it in 1956.Lumidyne, which Malina described in scientific-like style in journal articles as well as patent applications in the U.S., France, and the U.K., gave him a systematic approach to making art using movement and light.

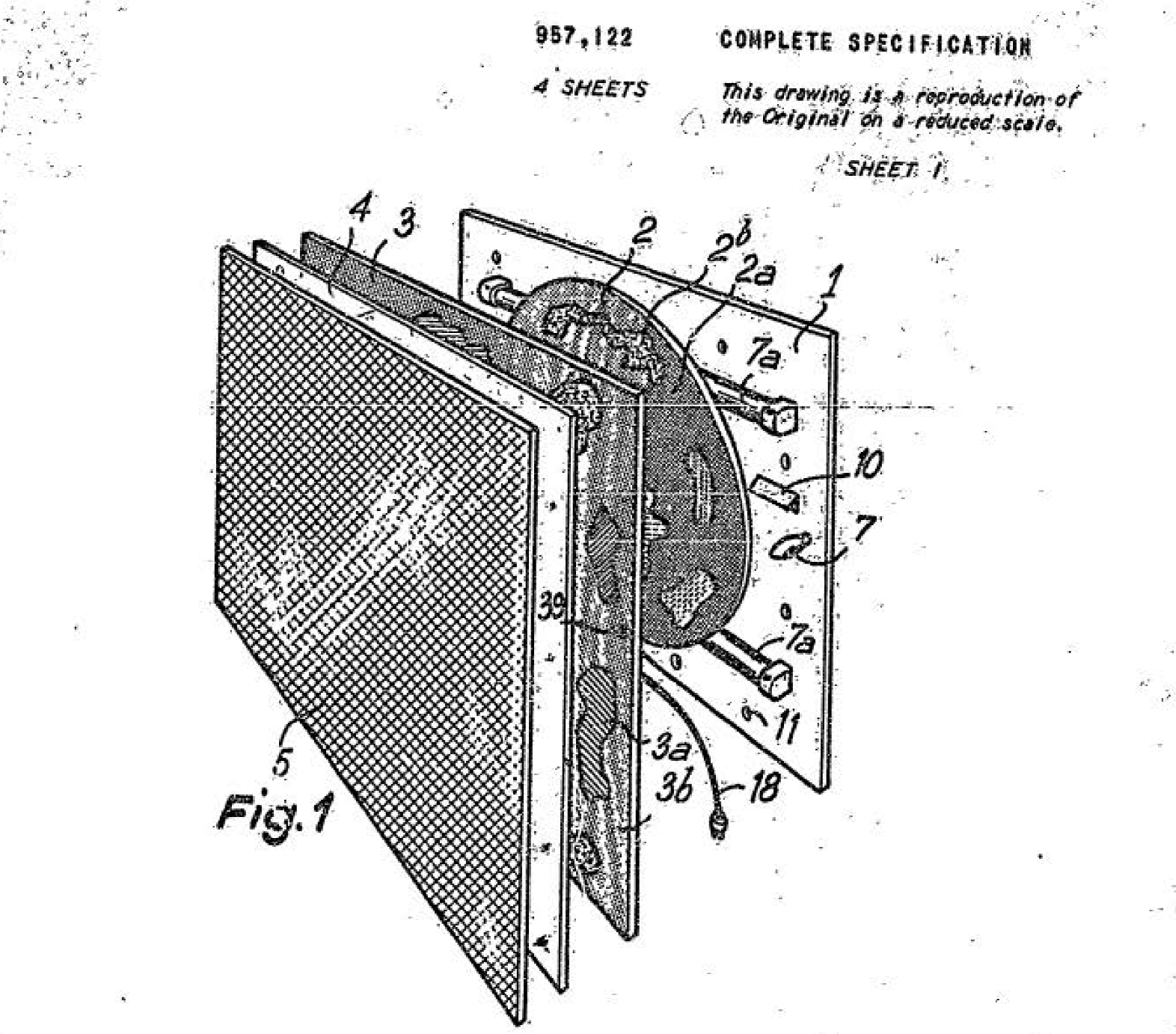

Malina was especially keen to introduce material from science and technology, particularly space exploration and astronomy, into contemporary visual arts. Even his early forays into painting incorporated “shock waves and fluid flow and paintings of airplanes and rockets.” As he moved away from traditional art techniques, Malina spent considerable time experimenting with new ways to create novel visual effects. In the mid-1950s, for example, Malina worked with a French electronics student to create what he called his Lumidyne technique. He made his first pieces using it in 1956.Lumidyne, which Malina described in scientific-like style in journal articles as well as patent applications in the U.S., France, and the U.K., gave him a systematic approach to making art using movement and light. The Lumidyne system was based on several interrelated parts: Light bulbs and electric motors were fixed to a wooden backboard. There were moving parts, which Malina called “rotors”, made of Plexiglas that he painted and connected to a motor. Fixed pieces of Plexiglas – the “stators” – were also painted. These parts were sandwiched between the backboard and a diffuser screen that faced the viewer.When switched on, a shifting subtle effect was created by the painted parts moving slowly in concert with the static pieces with light shining through them. The title of a 1961 patent application describes the resulting visual effect with Malina’s characteristic terse style: “Lighted, Animated, and Everchanging Picture Arrangement.” As was the case with his other techniques, the titles and topics of his art works using Lumidyne reflected his persistent engagement with scientific and space themes. The Arc, Orbiter, Sun Sparks, and Jodrell Bank are among the nearly 200 works Malina made using his Lumidyne system before he passed away in 1981.

The Lumidyne system was based on several interrelated parts: Light bulbs and electric motors were fixed to a wooden backboard. There were moving parts, which Malina called “rotors”, made of Plexiglas that he painted and connected to a motor. Fixed pieces of Plexiglas – the “stators” – were also painted. These parts were sandwiched between the backboard and a diffuser screen that faced the viewer.When switched on, a shifting subtle effect was created by the painted parts moving slowly in concert with the static pieces with light shining through them. The title of a 1961 patent application describes the resulting visual effect with Malina’s characteristic terse style: “Lighted, Animated, and Everchanging Picture Arrangement.” As was the case with his other techniques, the titles and topics of his art works using Lumidyne reflected his persistent engagement with scientific and space themes. The Arc, Orbiter, Sun Sparks, and Jodrell Bank are among the nearly 200 works Malina made using his Lumidyne system before he passed away in 1981. In 1965, the flamboyant millionaire (and socialist MP) Robert Maxwell commissioned Malina to make a statement piece for the entrance lobby of his company, Pergamon Press, a fast-growing British publisher of scientific journals based on Oxford. The result was a massive lumino-kinetic work Malina called Cosmos. Weighing several hundred pounds, Cosmos’ sheer size –over 70 square feet – commanded the attention of Pergamon’s visitors and staff.

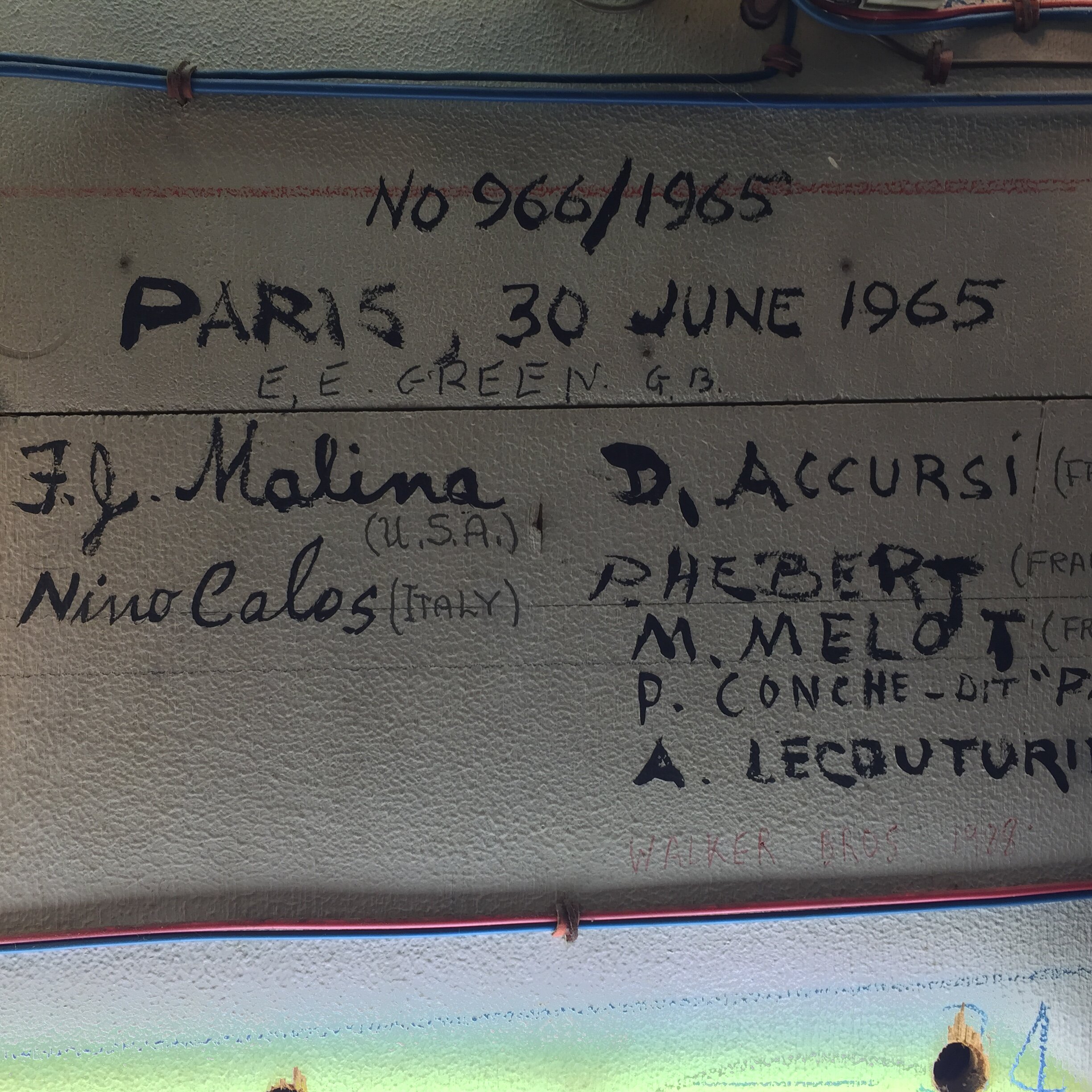

In 1965, the flamboyant millionaire (and socialist MP) Robert Maxwell commissioned Malina to make a statement piece for the entrance lobby of his company, Pergamon Press, a fast-growing British publisher of scientific journals based on Oxford. The result was a massive lumino-kinetic work Malina called Cosmos. Weighing several hundred pounds, Cosmos’ sheer size –over 70 square feet – commanded the attention of Pergamon’s visitors and staff. Malina began crafting Cosmos with sketches in his Paris workshop in the spring of 1965. A video has even survived which captures the process. Aided by a few technical assistants – the whole team signed their names inside the piece – Malina completed Cosmos in early July.

Malina began crafting Cosmos with sketches in his Paris workshop in the spring of 1965. A video has even survived which captures the process. Aided by a few technical assistants – the whole team signed their names inside the piece – Malina completed Cosmos in early July. Small electric motors slowly turned each of the rotor parts painted by Malina. 120 fluorescent tubes and light bulbs lit up the work. All of this was encased in a relatively thin wood and metal frame. When Malina had achieved the visual effects he wanted, the entire piece was disassembled and shipped to Oxford for a week-long installation at Pergamon’s building. And it's still there today...

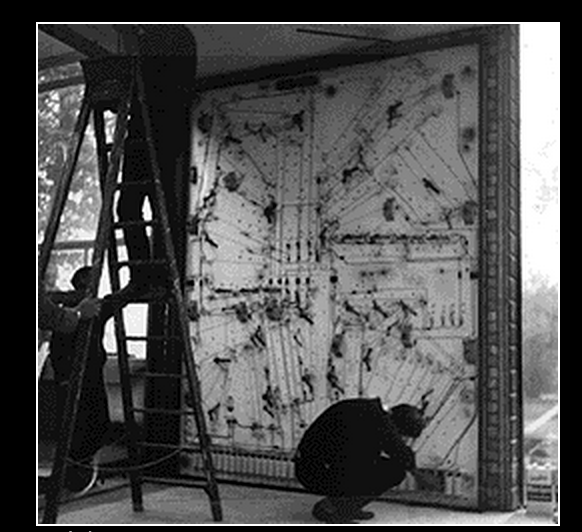

Small electric motors slowly turned each of the rotor parts painted by Malina. 120 fluorescent tubes and light bulbs lit up the work. All of this was encased in a relatively thin wood and metal frame. When Malina had achieved the visual effects he wanted, the entire piece was disassembled and shipped to Oxford for a week-long installation at Pergamon’s building. And it's still there today... In September 2015, I went to Oxford to see Malina’s Cosmos. It’s not an easy thing to do. Pergamon is no longer in business, Robert Maxwell is dead, and the building housing Cosmos is now part of Oxford Brookes University. The artwork resides in a small room, partitioned off from the original main lobby. It's used – from what I could tell – as a storage place for the campus radio station. Since it’s in a locked room on a private campus, I needed help getting access. Roger Malina, Frank’s son, put me in touch with Chris Jennings, an art professor at Brookes. Jennings knew the right people with the right keys and after a heroic effort with little advance notice, he met me at Brookes’ gate on a grey windy afternoon lightly whipped by rain.Imposing even when turned off, Cosmos is hardly recognizable at first as an art work. An electrician from campus came to switch Cosmos on for us. The lights switched on and immediately the many small electrical motors inside began to turn the painted rotors. For such a giant mechanical piece, it was surprisingly quiet. All I heard was the slight hum of fluorescent lights and an occasional click as one of the gears proved momentarily obstinate.

In September 2015, I went to Oxford to see Malina’s Cosmos. It’s not an easy thing to do. Pergamon is no longer in business, Robert Maxwell is dead, and the building housing Cosmos is now part of Oxford Brookes University. The artwork resides in a small room, partitioned off from the original main lobby. It's used – from what I could tell – as a storage place for the campus radio station. Since it’s in a locked room on a private campus, I needed help getting access. Roger Malina, Frank’s son, put me in touch with Chris Jennings, an art professor at Brookes. Jennings knew the right people with the right keys and after a heroic effort with little advance notice, he met me at Brookes’ gate on a grey windy afternoon lightly whipped by rain.Imposing even when turned off, Cosmos is hardly recognizable at first as an art work. An electrician from campus came to switch Cosmos on for us. The lights switched on and immediately the many small electrical motors inside began to turn the painted rotors. For such a giant mechanical piece, it was surprisingly quiet. All I heard was the slight hum of fluorescent lights and an occasional click as one of the gears proved momentarily obstinate. Frank Malina made Cosmos at the height of the Cold War-era space race. Yuri Gagarin and Alan Shepard had flown four years earlier and a satellite-based infrastructure was beginning to take shape. Astronomers were looking forward to an era of space telescopes observing across wavelengths inaccessible from earth and giving unparalleled resolution. This new techno-scientific activity meant that people were, as Malina wrote in 1966, “more conscious of the universe, both intellectually and visually” than at any other time since the Copernican Revolution. Malina imagined Cosmos as a reflection of a universe that he knew as neither static nor quiescent.

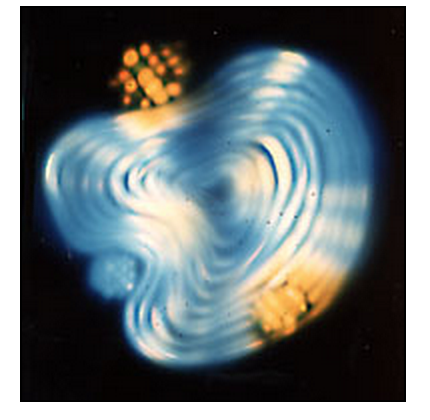

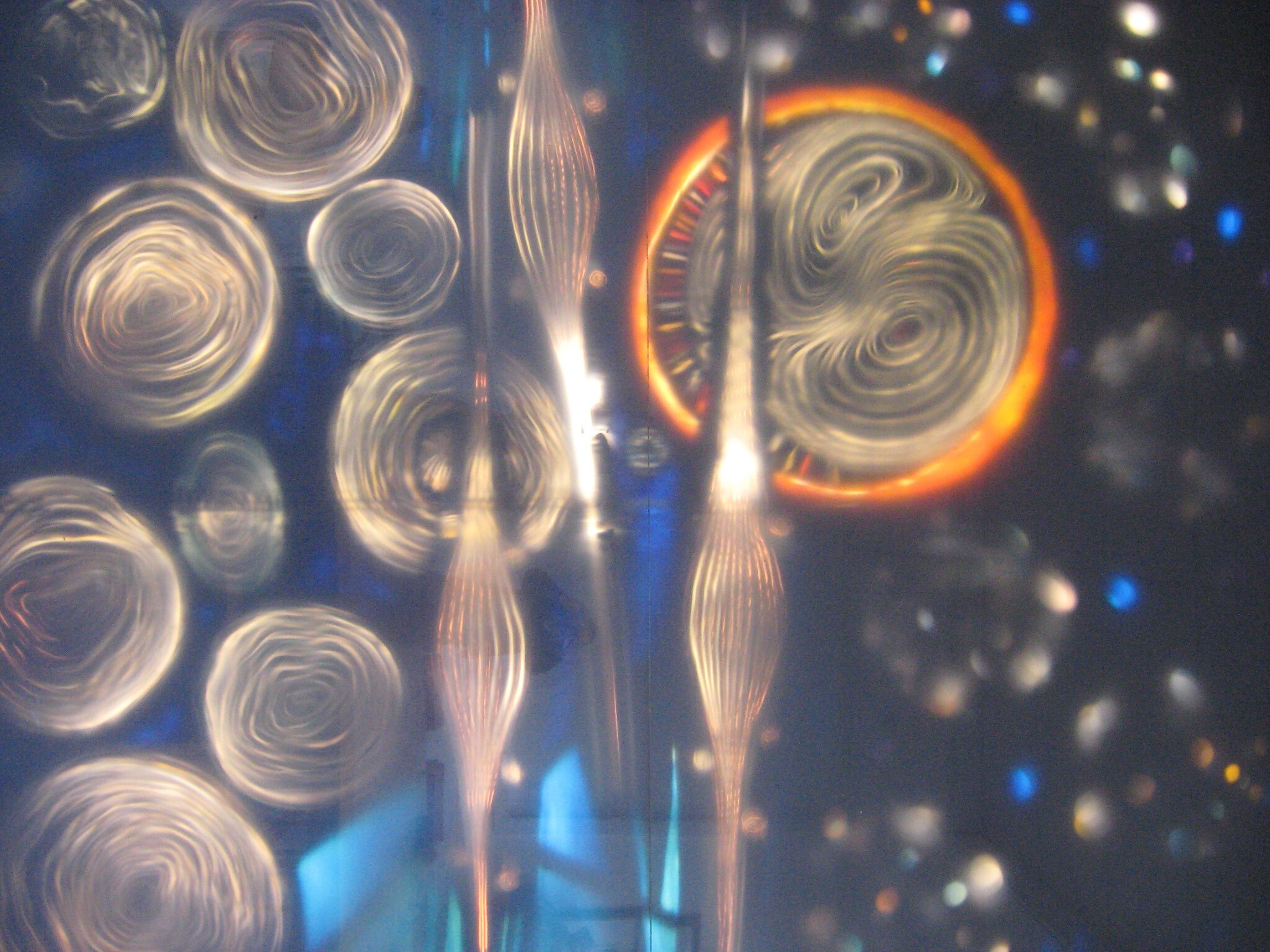

Frank Malina made Cosmos at the height of the Cold War-era space race. Yuri Gagarin and Alan Shepard had flown four years earlier and a satellite-based infrastructure was beginning to take shape. Astronomers were looking forward to an era of space telescopes observing across wavelengths inaccessible from earth and giving unparalleled resolution. This new techno-scientific activity meant that people were, as Malina wrote in 1966, “more conscious of the universe, both intellectually and visually” than at any other time since the Copernican Revolution. Malina imagined Cosmos as a reflection of a universe that he knew as neither static nor quiescent. The controlled motion of light and color reflected a view of an orderly Cosmos, however, one knowable to humans who were slowly starting to explore it. Malina abstracted his design from celestial shapes starting with the band of color at the bottom which Malina intended to represent colors seen by astronauts when orbiting the earth. Nine painted circular shapes represent the planets – Neil deGrasse Tyson & co. hadn’t yet killed Pluto – which hover below an abstracted sun presented in slowly changing shades of red, white, and orange.

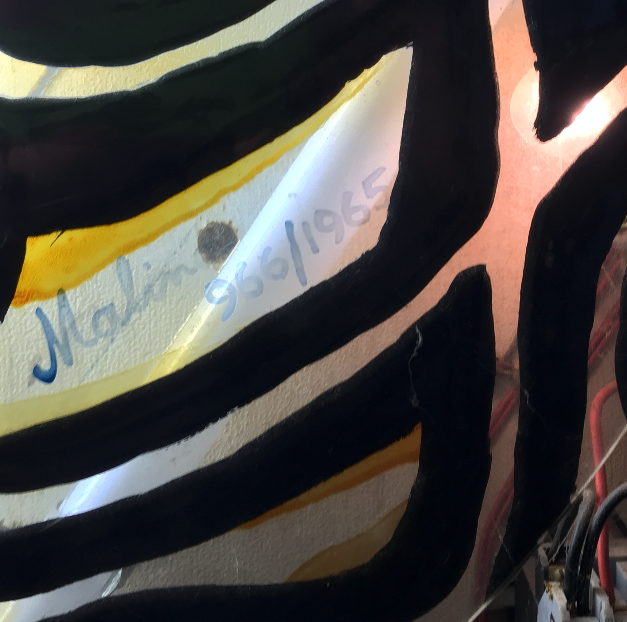

The controlled motion of light and color reflected a view of an orderly Cosmos, however, one knowable to humans who were slowly starting to explore it. Malina abstracted his design from celestial shapes starting with the band of color at the bottom which Malina intended to represent colors seen by astronauts when orbiting the earth. Nine painted circular shapes represent the planets – Neil deGrasse Tyson & co. hadn’t yet killed Pluto – which hover below an abstracted sun presented in slowly changing shades of red, white, and orange. Sitting between the sun and planets are three “nebulae,” executed in a manner similar to some of Malina’s earlier works – filaments of light moving back and forth. Finally, above the sun are scattered star clusters, another theme from Malina’s prior pieces, that slowly oscillate and pulse. The overall effect is elegant, continuous yet stately motion and shifting color.Malina wanted the piece to be an “expression of a ‘peaceful Cosmos’” while noting, of course, that the universe is anything but. “Events of cataclysmic proportion are constantly occurring” yet people were still willing to dare to “venture forth farther and farther” from the “planetary cradle,” he wrote. This profound shift in position and perspective was something that should challenge the artist. Either they would “find aesthetic significance” in explorations of space or “mock them in despair.”We also opened up Cosmos to inspect its interior. 1960s-era lights and switches share space with parts added during occasional repairs and upgrades. Malina had signed the various rotors and stators that he painted.

Sitting between the sun and planets are three “nebulae,” executed in a manner similar to some of Malina’s earlier works – filaments of light moving back and forth. Finally, above the sun are scattered star clusters, another theme from Malina’s prior pieces, that slowly oscillate and pulse. The overall effect is elegant, continuous yet stately motion and shifting color.Malina wanted the piece to be an “expression of a ‘peaceful Cosmos’” while noting, of course, that the universe is anything but. “Events of cataclysmic proportion are constantly occurring” yet people were still willing to dare to “venture forth farther and farther” from the “planetary cradle,” he wrote. This profound shift in position and perspective was something that should challenge the artist. Either they would “find aesthetic significance” in explorations of space or “mock them in despair.”We also opened up Cosmos to inspect its interior. 1960s-era lights and switches share space with parts added during occasional repairs and upgrades. Malina had signed the various rotors and stators that he painted. But their paint is beginning to flake and peel, presenting a challenge to the art conservator. And few of the rotors weren’t turning well.

But their paint is beginning to flake and peel, presenting a challenge to the art conservator. And few of the rotors weren’t turning well. The complexity of the art work – an ensemble of gears, chains, lights, switches, fuses, plastic disks, with wires running everywhere – surprised me. Compared with the quiet, contemplative mood the piece fosters, the inside of Cosmos is a very busy place.

The complexity of the art work – an ensemble of gears, chains, lights, switches, fuses, plastic disks, with wires running everywhere – surprised me. Compared with the quiet, contemplative mood the piece fosters, the inside of Cosmos is a very busy place. Malina created Cosmos as “silent almost static” panoramic view of the universe centered around our solar system. I stood in front of it for several minutes, watching the colors slowly form, dissolve, move, and shift. I took some last photos. And then, with a flick of the switch, Cosmos was dark again.

Malina created Cosmos as “silent almost static” panoramic view of the universe centered around our solar system. I stood in front of it for several minutes, watching the colors slowly form, dissolve, move, and shift. I took some last photos. And then, with a flick of the switch, Cosmos was dark again.