Lasers, Pot Smoke, and the "Visual Art of the Future"

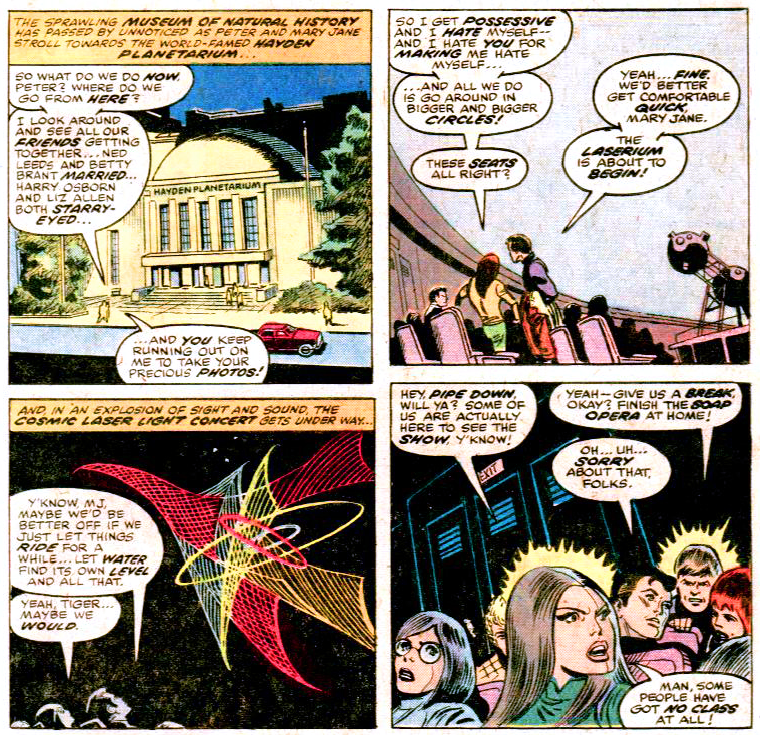

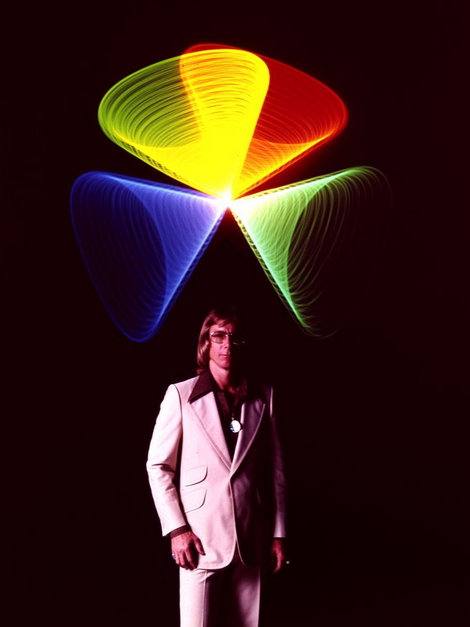

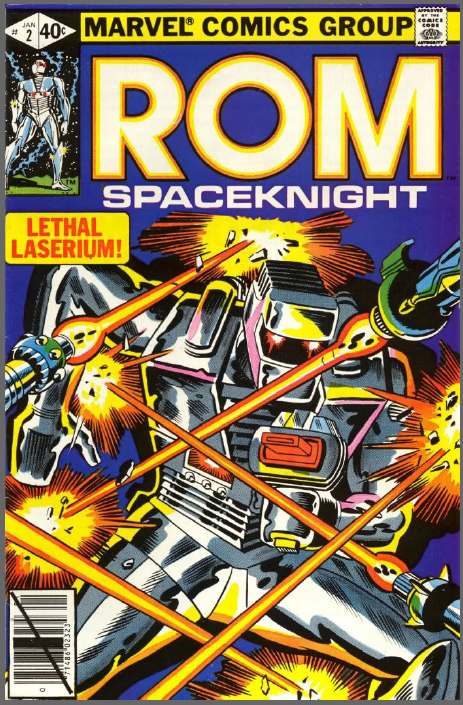

For some readers, one of the curious by-products of the 1960s-era art & technology movement might conjure up some hazy, hopefully fond memories - a toke in the VW, some comfy seats, Pink Floyd, and...lasers. Yes --- I'm talking Laserium. This image of wide-eyed stoners gazing in awe at laser beams synched to Led Zeppelin or the Electric Light Orchestra is at least how how the Amazing Spider Man and The Simpsons presented Laserium. Just ask Ben Stiller or The New York Times. OK - so straight-arrow Peter Parker probably wasn't indulging in reefer madness. But his girlfriend was named Mary Jane. Anyway...Laserium was the direct result of art-engineering experiments that physicist Elsa Garmire began to do at Caltech in the late 1960s. While in Pasadena, she combined her skill with lasers to a burgeoning interest in the art & technology movement that peaked around 1970.Garmire’s experimental live laser shows caught the attention of Ivan Dryer, a Los Angeles-based film maker. Before working in the entertainment business, Dryer was an “astronomy freak” but one more interested in the “mystiques of space…not the mechanics of it,” as he told People magazine in 1976. Before moving into the film industry, Dryer worked as a guide at Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles.

This image of wide-eyed stoners gazing in awe at laser beams synched to Led Zeppelin or the Electric Light Orchestra is at least how how the Amazing Spider Man and The Simpsons presented Laserium. Just ask Ben Stiller or The New York Times. OK - so straight-arrow Peter Parker probably wasn't indulging in reefer madness. But his girlfriend was named Mary Jane. Anyway...Laserium was the direct result of art-engineering experiments that physicist Elsa Garmire began to do at Caltech in the late 1960s. While in Pasadena, she combined her skill with lasers to a burgeoning interest in the art & technology movement that peaked around 1970.Garmire’s experimental live laser shows caught the attention of Ivan Dryer, a Los Angeles-based film maker. Before working in the entertainment business, Dryer was an “astronomy freak” but one more interested in the “mystiques of space…not the mechanics of it,” as he told People magazine in 1976. Before moving into the film industry, Dryer worked as a guide at Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. After seeing Garmire’s presentation, Dryer visited her Caltech lab. He and a colleague brought a camera with the intent of filming the “marvelous shapes and forms” that Garmire’s laser system generated. ((Recounted in “Applications Pioneer Interview: Ivan Dryer,” Laser and Applications, October 1986, 53-58.))

After seeing Garmire’s presentation, Dryer visited her Caltech lab. He and a colleague brought a camera with the intent of filming the “marvelous shapes and forms” that Garmire’s laser system generated. ((Recounted in “Applications Pioneer Interview: Ivan Dryer,” Laser and Applications, October 1986, 53-58.)) Dryer soon realized that filming Garmire’s laser images was aesthetically inferior to seeing the intensity and purity of their colors in person. In the fall of 1970, he arranged for a live and – to his eyes – captivating demonstration of Garmire’s system, accompanied by classical music, for Griffith staff in the observatory’s planetarium dome. The observatory management, however, was less enchanted with what they saw as entertainment, not education. Disappointed but still motivated, Dryer and Garmire co-founded a company in February 1971 called Laser Images Inc.. Riffing on the popularity of planetarium shows, they called their product “Laserium.” ((The idea of doing live laser shows did not originate with Dryer, et al. It was an idea, certainly, already in the air in the late 1960s. Lowell Cross, a multi-media artist, claims to have performed the first “public multi-color laser light show” in May 1969 at Mills College. Cross would go on to collaborate with Berkeley physicist Carson D. Jeffries and composer David Tudor to create a laser light show for the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka Expo '70.))For the next few years, Dryer and Garmire worked intermittently to perfect their laser show and attract interest. A representative from Spectra-Physics, a southern California company that made some of the first commercial lasers, loaned them a krypton laser system that could produce multiple colors. In June 1973, they invited the new director of Griffith Observatory William Kaufmann III, to see an improved demonstration at Garmire’s lab. Kauffmann, then in his early 30s, had a more liberal view of what the public might want to see at the observatory and he arranged for Dryer and McDonald to have access to the planetarium dome.In mid-November 1973, spurred by Dryer’s appearance on a morning television show, some 700 people showed up at Griffith to see the debut of what became known simply as Laserium. Classical and art rock music - Pink Floyd's prog rock epics would prove to be an audience fave - provided the soundtrack as multi-color laser images were projected in real-time on the planetarium’s starry background.

Dryer soon realized that filming Garmire’s laser images was aesthetically inferior to seeing the intensity and purity of their colors in person. In the fall of 1970, he arranged for a live and – to his eyes – captivating demonstration of Garmire’s system, accompanied by classical music, for Griffith staff in the observatory’s planetarium dome. The observatory management, however, was less enchanted with what they saw as entertainment, not education. Disappointed but still motivated, Dryer and Garmire co-founded a company in February 1971 called Laser Images Inc.. Riffing on the popularity of planetarium shows, they called their product “Laserium.” ((The idea of doing live laser shows did not originate with Dryer, et al. It was an idea, certainly, already in the air in the late 1960s. Lowell Cross, a multi-media artist, claims to have performed the first “public multi-color laser light show” in May 1969 at Mills College. Cross would go on to collaborate with Berkeley physicist Carson D. Jeffries and composer David Tudor to create a laser light show for the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka Expo '70.))For the next few years, Dryer and Garmire worked intermittently to perfect their laser show and attract interest. A representative from Spectra-Physics, a southern California company that made some of the first commercial lasers, loaned them a krypton laser system that could produce multiple colors. In June 1973, they invited the new director of Griffith Observatory William Kaufmann III, to see an improved demonstration at Garmire’s lab. Kauffmann, then in his early 30s, had a more liberal view of what the public might want to see at the observatory and he arranged for Dryer and McDonald to have access to the planetarium dome.In mid-November 1973, spurred by Dryer’s appearance on a morning television show, some 700 people showed up at Griffith to see the debut of what became known simply as Laserium. Classical and art rock music - Pink Floyd's prog rock epics would prove to be an audience fave - provided the soundtrack as multi-color laser images were projected in real-time on the planetarium’s starry background. Word of mouth helped expand the audience and, by the time the initial four week engagement at Griffith ended, hundreds of people were being turned away for laser shows. Other observatory directors in cities like Denver and New York City were intrigued.

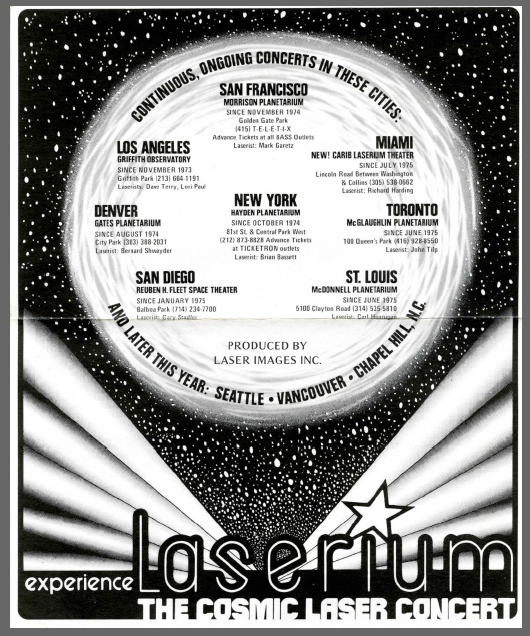

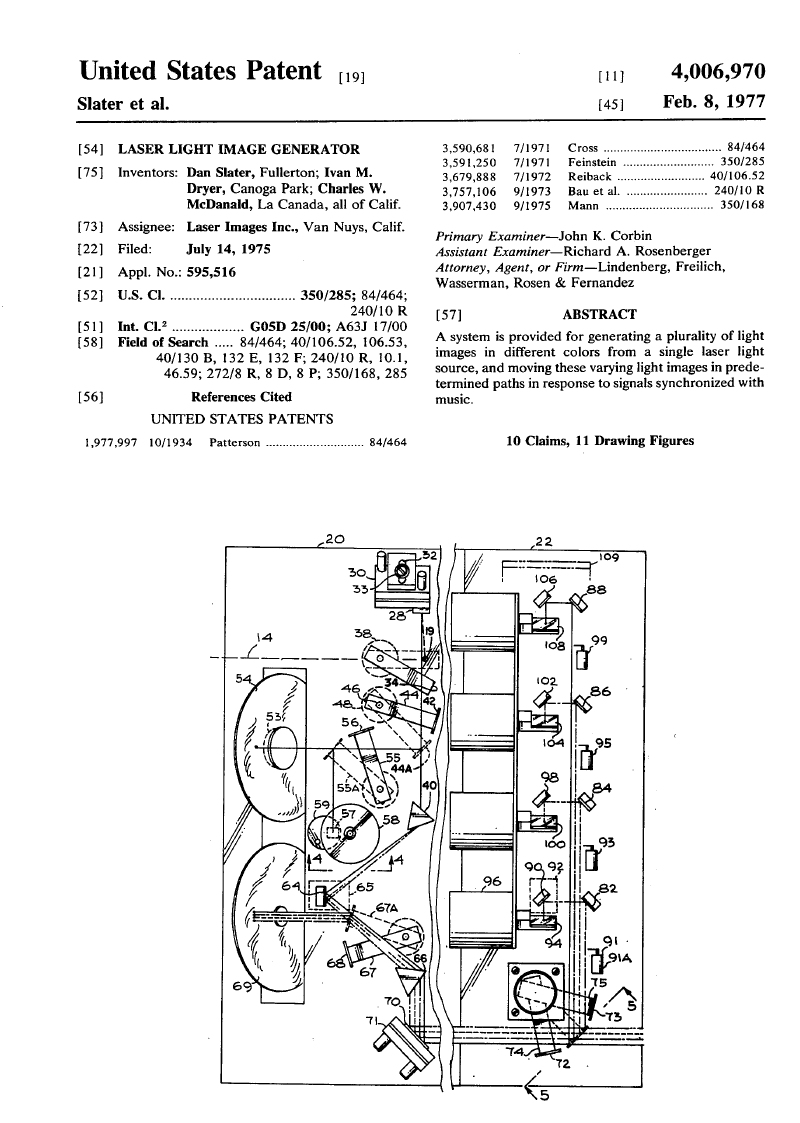

Word of mouth helped expand the audience and, by the time the initial four week engagement at Griffith ended, hundreds of people were being turned away for laser shows. Other observatory directors in cities like Denver and New York City were intrigued. By 1977, Dryer’s growing team of live laser performers were putting on shows in more than 15 cities in the U.S. and abroad and Laserium was a registered trademark. ((Garmire’s involvement with Laserium was the end of her collaboration with artists. She left the company amicably in 1974 and she pursued a successful scientific career in laser science and physics at the University of Southern California (1974) and then Dartmouth College (1995), eventually becoming a dean of engineering at Dartmouth.))Beginning with custom equipment, eventually Laserium was based around a standard system, details of which are preserved in the patent application Dryer and two colleagues filed in July 1975 for a “laser light image generator” that can create a “plurality of light images in different colors from a single laser light.” ((Dan Slater, Ivan M. Dryer, and Charles W. McDonald. “Laser Light Image Generator.” U.S. Patent 4,006,970 , filed 14 July 1975, issued 8 February 1977.))

By 1977, Dryer’s growing team of live laser performers were putting on shows in more than 15 cities in the U.S. and abroad and Laserium was a registered trademark. ((Garmire’s involvement with Laserium was the end of her collaboration with artists. She left the company amicably in 1974 and she pursued a successful scientific career in laser science and physics at the University of Southern California (1974) and then Dartmouth College (1995), eventually becoming a dean of engineering at Dartmouth.))Beginning with custom equipment, eventually Laserium was based around a standard system, details of which are preserved in the patent application Dryer and two colleagues filed in July 1975 for a “laser light image generator” that can create a “plurality of light images in different colors from a single laser light.” ((Dan Slater, Ivan M. Dryer, and Charles W. McDonald. “Laser Light Image Generator.” U.S. Patent 4,006,970 , filed 14 July 1975, issued 8 February 1977.)) The projection unit was rectangular in shape, about 2’ by 6’ by 3’. The heart of the system was a one-watt krypton gas laser which would be split by prisms into four colors. Other optics, scanners, and oscillators allowed for extremely rapid play of images, closed linear shapes, Lissajous figures, and so on. An operator sat at a console where she could access a variety of switches and joysticks to play the “instrument.”

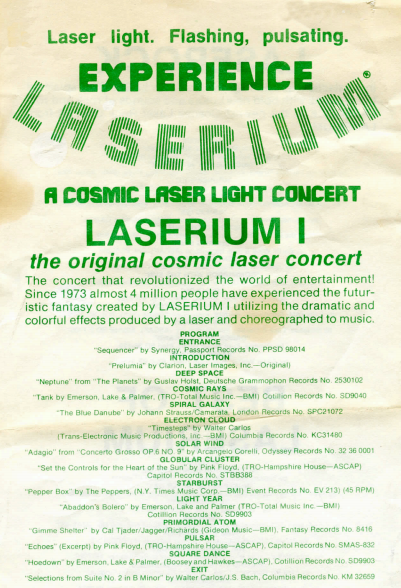

The projection unit was rectangular in shape, about 2’ by 6’ by 3’. The heart of the system was a one-watt krypton gas laser which would be split by prisms into four colors. Other optics, scanners, and oscillators allowed for extremely rapid play of images, closed linear shapes, Lissajous figures, and so on. An operator sat at a console where she could access a variety of switches and joysticks to play the “instrument.” A four-track tape deck had music in stereo as well as audio for the show’s introduction and narration. For new laserists, a “teach track” helped them learn the system and the best timing for performances. The basic format of each show was preprogrammed by the “laserist” who had considerable opportunity to vary and change the tempo and image sequences. Laserium shows were performed live and the quality of them, as well as the audience’s response, depended on the skill and imagination of the system operator.

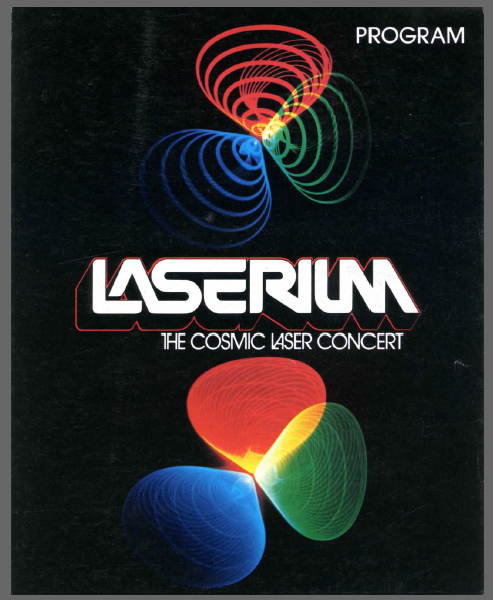

A four-track tape deck had music in stereo as well as audio for the show’s introduction and narration. For new laserists, a “teach track” helped them learn the system and the best timing for performances. The basic format of each show was preprogrammed by the “laserist” who had considerable opportunity to vary and change the tempo and image sequences. Laserium shows were performed live and the quality of them, as well as the audience’s response, depended on the skill and imagination of the system operator. Laserium had a broad appeal - stoners, geeks, and planetarium junkies all turned out to see shows. Its popularity was no doubt enhanced by the relative novelty of lasers for the general public in the mid-1970s. The 1977 film Star Wars added to people's interest in all things laser. A sense of the excitement can be seen in this 1976 program.

Laserium had a broad appeal - stoners, geeks, and planetarium junkies all turned out to see shows. Its popularity was no doubt enhanced by the relative novelty of lasers for the general public in the mid-1970s. The 1977 film Star Wars added to people's interest in all things laser. A sense of the excitement can be seen in this 1976 program. Just as planetarium shows have helped popularize astronomy, Laserium can be seen as a public display of laser technology, its roots traceable back to 19th century displays of electricity and electrical effects.It was not without its aesthetic admirers. One art writer, for example, referred to experiments with laser projection as the “seeds of what will become the high, universally acclaimed visual art of the future.” ((Andrew Kagan, “Laserium: New Light on an Ancient Vision,” Arts Magazine, March 1978.)) Given Laserium’s penchant for attracting attendees whose appreciation of choreographed laser light was chemically enhanced, “high” visual art takes on another meaning as well.After peaking in the late 1970s when some 70 people worked for the company, Laserium slowly faded in popularity. Often lampooned as the preferred entertainment of pot heads and LSD trippers, we can also see Laserium as the somewhat disreputable cousin of the venerable planetarium show. Nonetheless, by 2002, some 20 million people around the world had seen a Laserium show – its run at Griffith lasted some 28 years – and its idiosyncratic blend of music and spectacle had become part of popular culture.

Just as planetarium shows have helped popularize astronomy, Laserium can be seen as a public display of laser technology, its roots traceable back to 19th century displays of electricity and electrical effects.It was not without its aesthetic admirers. One art writer, for example, referred to experiments with laser projection as the “seeds of what will become the high, universally acclaimed visual art of the future.” ((Andrew Kagan, “Laserium: New Light on an Ancient Vision,” Arts Magazine, March 1978.)) Given Laserium’s penchant for attracting attendees whose appreciation of choreographed laser light was chemically enhanced, “high” visual art takes on another meaning as well.After peaking in the late 1970s when some 70 people worked for the company, Laserium slowly faded in popularity. Often lampooned as the preferred entertainment of pot heads and LSD trippers, we can also see Laserium as the somewhat disreputable cousin of the venerable planetarium show. Nonetheless, by 2002, some 20 million people around the world had seen a Laserium show – its run at Griffith lasted some 28 years – and its idiosyncratic blend of music and spectacle had become part of popular culture. One of the goals of formal artist-engineer collaborations was to generate technical "fallout" - ideas that could benefit corporate patrons - as well as spinoffs of new companies. Laserium was one of the most commercially successful results from the fecund artist-engineer collaborations of the late 1960s.More importantly, Laserium offers another data point that says we can no longer think of the late 1960s and early 1970s as an “anti-science” or “anti-technology” period. A more informed and nuanced reading tells us that engineers, artists, and society in general sought and found alternative forms of science and technology. Laserium was a colorful off-shoot of this search for a different, groovier, science.

One of the goals of formal artist-engineer collaborations was to generate technical "fallout" - ideas that could benefit corporate patrons - as well as spinoffs of new companies. Laserium was one of the most commercially successful results from the fecund artist-engineer collaborations of the late 1960s.More importantly, Laserium offers another data point that says we can no longer think of the late 1960s and early 1970s as an “anti-science” or “anti-technology” period. A more informed and nuanced reading tells us that engineers, artists, and society in general sought and found alternative forms of science and technology. Laserium was a colorful off-shoot of this search for a different, groovier, science.