Project Moneyshot?

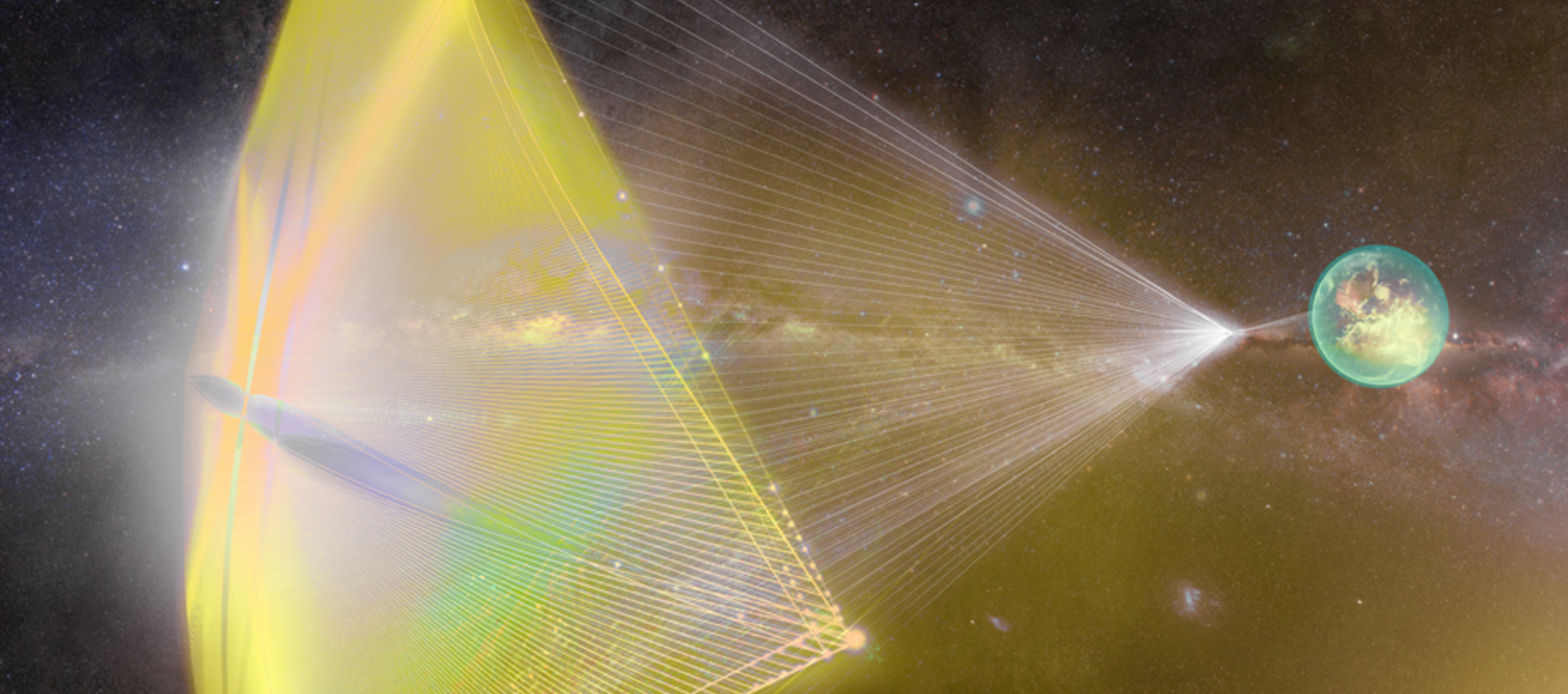

Yesterday – the anniversary of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s pioneering spaceflight – Russian billionaire Yuri Milner made international headlines with his announcement of an initial $100 million investment called the Breakthrough Starshot. Starshot’s proposed plan would unfold like this: sometime, decades hence, a rocket ship would deliver a thousand or more craft, each about the size of deck of cards, into space. This swarm of spacecraft would unfurl tiny solar sails. Then, a giant laser array on Earth would send beams of intense coherent light, accelerating the fleet up to about 20% the speed of light.

Starshot’s proposed plan would unfold like this: sometime, decades hence, a rocket ship would deliver a thousand or more craft, each about the size of deck of cards, into space. This swarm of spacecraft would unfurl tiny solar sails. Then, a giant laser array on Earth would send beams of intense coherent light, accelerating the fleet up to about 20% the speed of light. Assuming accurate navigation, in about 20 years, the space swarm would arrive at Alpha Centauri, some 4.37 light years from us. The craft would hurtle past the star system, beaming information and pictures back to Earth. Estimated total cost? Somewhere between $5-10 billion.Russian billionaire? Check. Giant laser? Check. Someone get Ian Fleming’s estate on the phone…Milner fits perfectly into the category of historical actors I have called visioneers: he possesses an expansive view of how his technological projects could alter the future; he has a scientific background; and he has the means and skill to promote and publicize his ideas, taking them to a wide audience. And – unlike the people I wrote about in my book – Milner has the added benefit of gazillions of dollars to fuel his dream.When I read about Breakthrough Starshot in The New York Times this morning, more than anything I was drawn to the comments (yes, I read them). Other than those people who wrote to say the whole idea was stupid – a not terribly helpful critique – many remarks fell into two main categories.Group One said (paraphrasing): “This is an awesome idea. It will inspire people to study science. Humanity needs big ideas. We’re a curious species. We should, nay, we need to do this. Ad astra!!”Group Two wasn't so boosterish: “We have real problems here and now. This money could be better spent right here in our communities. Moreover, isn’t this just part of the larger plan of the rich and powerful seeking ways off this rock when everything heads south? Tax these people now!”More than anything, people’s reactions reminded me of public debates in the mid-1970s about the future possibilities of building large-scale settlements that would float freely out in space. Associated most closely with the visioneering ideas of Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill, the idea of space colonies provoked a very similar response four decades ago.A good sense of this polarization can be found in the pages of a book that appeared in 1977. Edited by Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, Space Colonies presented a myriad array of opinions and responses from experts, pundits, and ordinary citizens about O’Neill’s proposed off-world habitats.

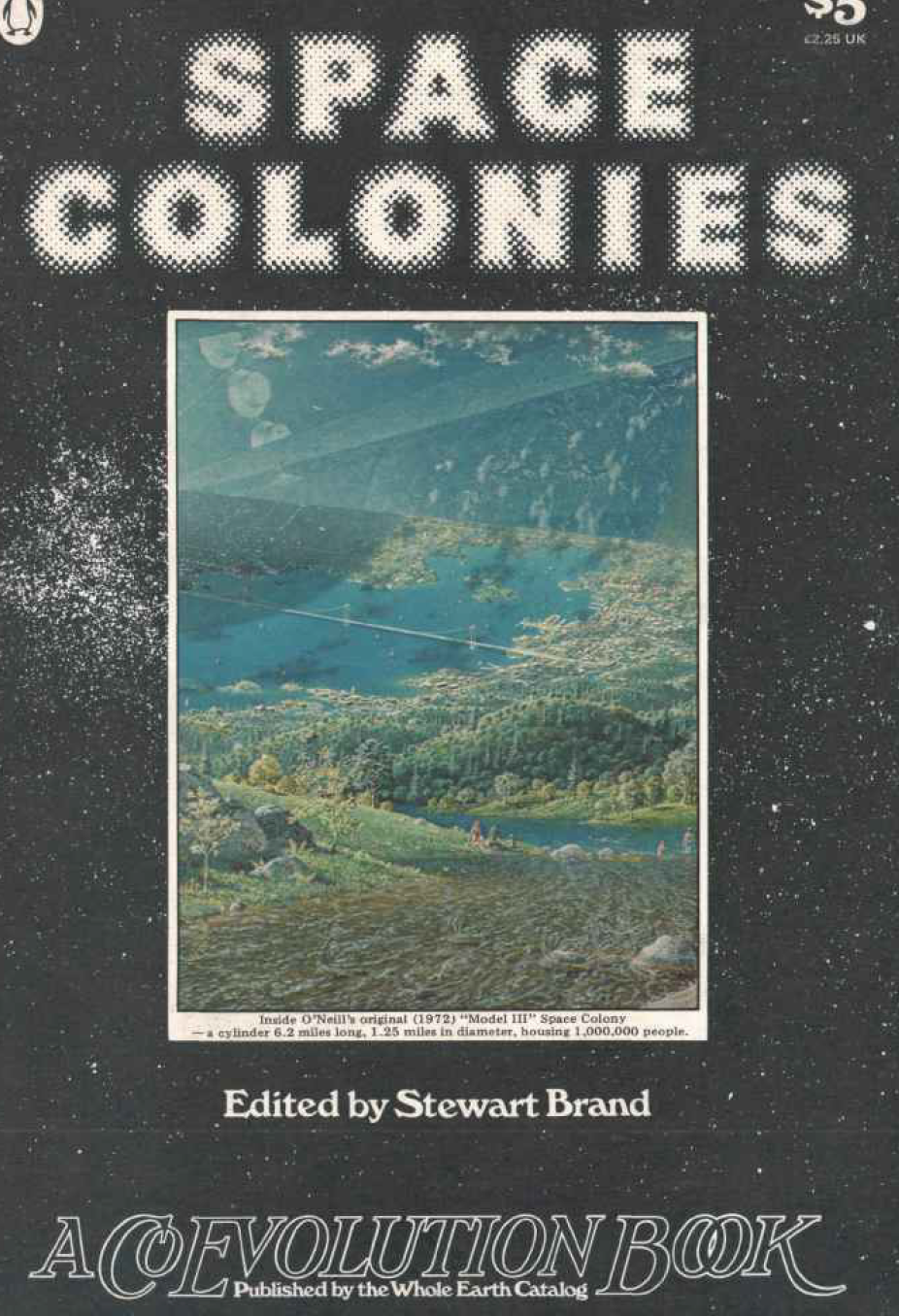

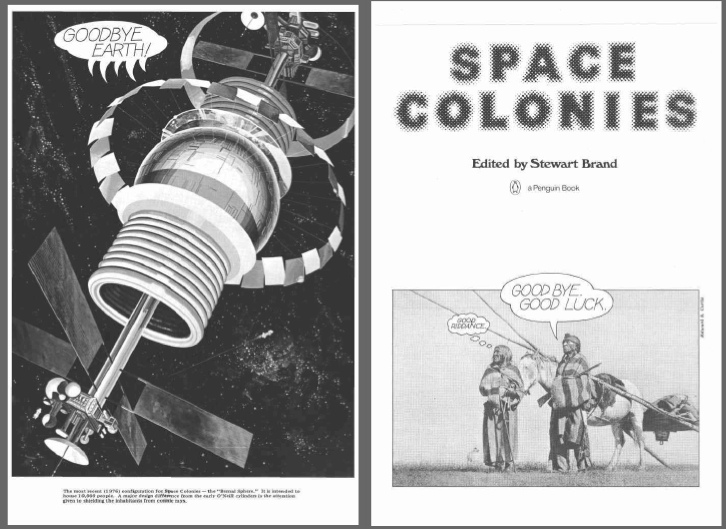

Assuming accurate navigation, in about 20 years, the space swarm would arrive at Alpha Centauri, some 4.37 light years from us. The craft would hurtle past the star system, beaming information and pictures back to Earth. Estimated total cost? Somewhere between $5-10 billion.Russian billionaire? Check. Giant laser? Check. Someone get Ian Fleming’s estate on the phone…Milner fits perfectly into the category of historical actors I have called visioneers: he possesses an expansive view of how his technological projects could alter the future; he has a scientific background; and he has the means and skill to promote and publicize his ideas, taking them to a wide audience. And – unlike the people I wrote about in my book – Milner has the added benefit of gazillions of dollars to fuel his dream.When I read about Breakthrough Starshot in The New York Times this morning, more than anything I was drawn to the comments (yes, I read them). Other than those people who wrote to say the whole idea was stupid – a not terribly helpful critique – many remarks fell into two main categories.Group One said (paraphrasing): “This is an awesome idea. It will inspire people to study science. Humanity needs big ideas. We’re a curious species. We should, nay, we need to do this. Ad astra!!”Group Two wasn't so boosterish: “We have real problems here and now. This money could be better spent right here in our communities. Moreover, isn’t this just part of the larger plan of the rich and powerful seeking ways off this rock when everything heads south? Tax these people now!”More than anything, people’s reactions reminded me of public debates in the mid-1970s about the future possibilities of building large-scale settlements that would float freely out in space. Associated most closely with the visioneering ideas of Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill, the idea of space colonies provoked a very similar response four decades ago.A good sense of this polarization can be found in the pages of a book that appeared in 1977. Edited by Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, Space Colonies presented a myriad array of opinions and responses from experts, pundits, and ordinary citizens about O’Neill’s proposed off-world habitats. About four out of five correspondents who wrote to Brand viewed the idea of space colonies favorably. Some imagined space settlements as an extension of the groovy “back to land” lifestyle that was popular in the 1970s. (This was ironic given that space settlements would be hugely intensive in terms of resources and capital and require Apollo-like management to succeed.) More sadly, a few people expressed fatalism and even a sense of desperation about the future need for settlements in space: “Whatever I can do,” said one, “may help my beautiful daughter to slip away from this failing civilization here on Earth.”But space colonies also provoked outrage among some readers. Spending such huge amounts of money to circumvent the planet’s limits struck one reader as “well thought out, rational, very alluring” and also “quite mad.” It appeared as technological fix taken to its logical extreme. For these people, the idea of space settlements violated British economist E.F. Schumacher’s “small is beautiful” philosophy and his ideals of small-scale appropriate technology. Others detected signs of a massive new federal program and the military-industrial complex at work – “the same old technological whiz-bang and dreary imperialism,” one person said.An illustration in Brand’s book captured readers’ split opinions. One page showed an artist’s colorful rendition of a spherical space settlement. The facing page presented a 19th century photograph of a Native American couple who appeared to be gazing at it – the text added above the man’s head said, “Goodbye. Good luck.” The woman’s reaction? “Good riddance.”

About four out of five correspondents who wrote to Brand viewed the idea of space colonies favorably. Some imagined space settlements as an extension of the groovy “back to land” lifestyle that was popular in the 1970s. (This was ironic given that space settlements would be hugely intensive in terms of resources and capital and require Apollo-like management to succeed.) More sadly, a few people expressed fatalism and even a sense of desperation about the future need for settlements in space: “Whatever I can do,” said one, “may help my beautiful daughter to slip away from this failing civilization here on Earth.”But space colonies also provoked outrage among some readers. Spending such huge amounts of money to circumvent the planet’s limits struck one reader as “well thought out, rational, very alluring” and also “quite mad.” It appeared as technological fix taken to its logical extreme. For these people, the idea of space settlements violated British economist E.F. Schumacher’s “small is beautiful” philosophy and his ideals of small-scale appropriate technology. Others detected signs of a massive new federal program and the military-industrial complex at work – “the same old technological whiz-bang and dreary imperialism,” one person said.An illustration in Brand’s book captured readers’ split opinions. One page showed an artist’s colorful rendition of a spherical space settlement. The facing page presented a 19th century photograph of a Native American couple who appeared to be gazing at it – the text added above the man’s head said, “Goodbye. Good luck.” The woman’s reaction? “Good riddance.” I still believe visioneers as a species are essential components to a healthy technological or innovation ecosystem. But, since my book appeared in 2013, I’ve attenuated my enthusiasm. Specifically, I've become increasingly skeptical of many of the individuals who fit the category I described. This is, in part, because so many of them – Milner, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, et al. – are white males with Silicon Valley connections and an Ivy League pedigree. Where are the women and people of color? And what's with the space obsession?I’m old enough to remember watching the final Apollo missions on television. Part of me loves the idea of spacecraft speeding off to another star system. But another part of me has to agree with those who suggested less-than-radical things like fixing the water supply in Flint or repairing America's infrastructure. Sure, it’s not as glitzy-sexy as spacecraft and giant lasers. But we should want expansive visions of technological possibilities both here and propelling us out to the stars. That’s a future I’d love to see. Even if it does have a giant laser in it.

I still believe visioneers as a species are essential components to a healthy technological or innovation ecosystem. But, since my book appeared in 2013, I’ve attenuated my enthusiasm. Specifically, I've become increasingly skeptical of many of the individuals who fit the category I described. This is, in part, because so many of them – Milner, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, et al. – are white males with Silicon Valley connections and an Ivy League pedigree. Where are the women and people of color? And what's with the space obsession?I’m old enough to remember watching the final Apollo missions on television. Part of me loves the idea of spacecraft speeding off to another star system. But another part of me has to agree with those who suggested less-than-radical things like fixing the water supply in Flint or repairing America's infrastructure. Sure, it’s not as glitzy-sexy as spacecraft and giant lasers. But we should want expansive visions of technological possibilities both here and propelling us out to the stars. That’s a future I’d love to see. Even if it does have a giant laser in it.