Fog & Physics

Every day, hundreds of visitors to the recently relocated Exploratorium in San Francisco cross a pedestrian bridge between Piers 15 and 17. Here, if the timing is right, they can encounter and play within an immersive fog sculpture. "Fog Bridge" was conceived and designed by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya. Its existence as interplay between art, aesthetics, and physics can be traced back more than four decades. Nakaya's work began in the 1960s during the brief but potent flowering of formal collaborations between artists and engineers. A signature piece of this "art & tech" movement was the Pavilion. Initiated and sponsored by Pepsi-Cola, the multi-media experience that was the Pavilion opened in the spring of 1970 as part of Expo '70 in Osaka. In an era marked by Big Science - typified by expensive large-scale research collaborations - we can see the Pavilion as the aesthetic analog: Big Art.

Nakaya's work began in the 1960s during the brief but potent flowering of formal collaborations between artists and engineers. A signature piece of this "art & tech" movement was the Pavilion. Initiated and sponsored by Pepsi-Cola, the multi-media experience that was the Pavilion opened in the spring of 1970 as part of Expo '70 in Osaka. In an era marked by Big Science - typified by expensive large-scale research collaborations - we can see the Pavilion as the aesthetic analog: Big Art. Organized by Experiments in Art and Technology (or E.A.T.), a group co-founded in 1966 by Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver, scores of artists, engineers, and staff worked to bring the Pavilion into existence. Meanwhile, Pepsi poured over some $1.2 million into funding their work. ((Over $7 million in today's currency.))

Organized by Experiments in Art and Technology (or E.A.T.), a group co-founded in 1966 by Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver, scores of artists, engineers, and staff worked to bring the Pavilion into existence. Meanwhile, Pepsi poured over some $1.2 million into funding their work. ((Over $7 million in today's currency.)) The Pavilion was the apogee of the "art & tech" movement of the 1960s and, as Klüver often pointed out, one of the grandest art projects of the 20th century. Visually, the most striking thing about the Pavilion, at least from the outside, was how much of it you couldn't see. This is because the designers of Pavilion decided early on to shroud (perhaps hide?) the Pavilion's crumpled geodesic-style dome - what one E.A.T. member lampooned as a "Buckled Fuller dome" - with fog. ((This choice stemmed, in part, from the fact that Klüver and the other E.A.T. members disliked the Pavilion's architecture, which Pepsi selected and a Japanese firm produced. Nakaya's fog offered a way to obscure it.)) This was no natural fog however, but an artificially generated veil of atomized water droplets crafted by Nakaya and engineered by a small California company.

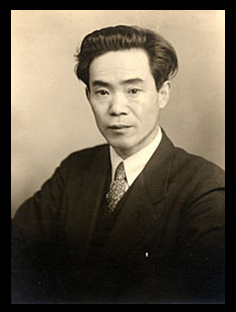

The Pavilion was the apogee of the "art & tech" movement of the 1960s and, as Klüver often pointed out, one of the grandest art projects of the 20th century. Visually, the most striking thing about the Pavilion, at least from the outside, was how much of it you couldn't see. This is because the designers of Pavilion decided early on to shroud (perhaps hide?) the Pavilion's crumpled geodesic-style dome - what one E.A.T. member lampooned as a "Buckled Fuller dome" - with fog. ((This choice stemmed, in part, from the fact that Klüver and the other E.A.T. members disliked the Pavilion's architecture, which Pepsi selected and a Japanese firm produced. Nakaya's fog offered a way to obscure it.)) This was no natural fog however, but an artificially generated veil of atomized water droplets crafted by Nakaya and engineered by a small California company. Born in Sapporo in 1933, Fujiko Nakaya was the daughter of Japanese physicist Ukichiro Nakaya. He became well-known in mid-20th century for his path-breaking research on the science of snow.

Born in Sapporo in 1933, Fujiko Nakaya was the daughter of Japanese physicist Ukichiro Nakaya. He became well-known in mid-20th century for his path-breaking research on the science of snow. For decades, Nakaya - recently featured in a Google doodle - worked to perfect lab techniques for making artificial snow crystals. He then rigorously studied their structure and developed a classification system for them. ((I find Nakaya's snow research just fascinating;there's a good graduate student project here...))

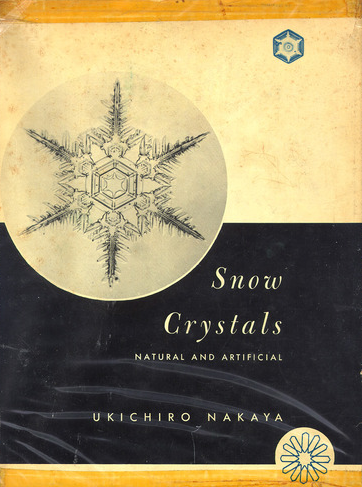

For decades, Nakaya - recently featured in a Google doodle - worked to perfect lab techniques for making artificial snow crystals. He then rigorously studied their structure and developed a classification system for them. ((I find Nakaya's snow research just fascinating;there's a good graduate student project here...)) The culmination of Ukichiro Nakaya's work was a 1954 book published by Harvard University Press called Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial. Snow flakes, he wrote, were "hieroglyphs sent from the sky."

The culmination of Ukichiro Nakaya's work was a 1954 book published by Harvard University Press called Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial. Snow flakes, he wrote, were "hieroglyphs sent from the sky." His daughter, Fujiko, took her father's empirical approach to understanding a specific meteorological phenomenon and applied it to art. After graduating from college in 1959 at Northwestern University, she spent two years at the Sorbonne in Paris where she studied painting. Around 1966, she met Klüver and participated in the (in)famous 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering show at the 69th Street Armory in New York City. When Klüver and E.A.T. got the nod from Pepsi to do the Pavilion, Nakaya became a central person in the project. Besides handling logistics and smoothing over Japanese-American interactions, in Osaka, she designed the fog sculpture that would surround the building.Producing fog from pure water isn’t easy however. In nature, fog is often produced when the air temperature drops until the air is saturated and water droplets condense. One way to generate artificial fog would be to boil water which, when surrounded by cooler air, condenses. Another would be to dramatically cool the Pavilion's roof. Both of these approaches would require huge amounts of energy. But there was a third method, the one that Nakaya wanted to do. Fog can also be made by atomizing water i.e. basically spraying tiny droplets of water into the atmosphere.To realize her aesthetic goal, Nakaya struck up a collaboration with a physicist based in Southern California. Thomas R. Mee moved to the Pasadena area after working on a variety of weather modification projects for Cornell University in the early 1960s. After working a few years for Meteorological Research Inc.. ((This company was started in 1951 by Paul MacCready (1925-2007), a Caltech graduate who later became famous for designing and building the Gossamer Condor, a human-powered aircraft. MacCready later started another southern California company, AeroVironment, which today is one of the largest manufacturers of unmanned aerial vehicles (“drones”).)) In 1969, he started his own company. Initially, Mee Industries Inc. made niche instrumentation for weather and pollution studies.

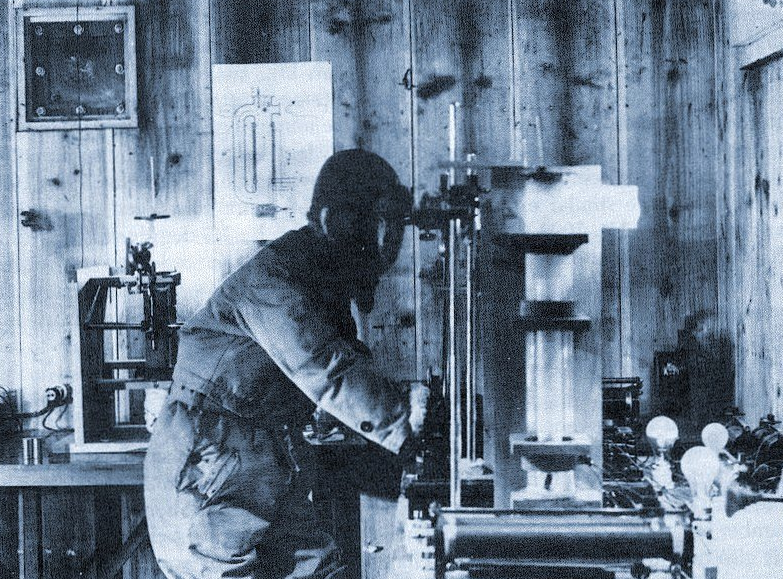

His daughter, Fujiko, took her father's empirical approach to understanding a specific meteorological phenomenon and applied it to art. After graduating from college in 1959 at Northwestern University, she spent two years at the Sorbonne in Paris where she studied painting. Around 1966, she met Klüver and participated in the (in)famous 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering show at the 69th Street Armory in New York City. When Klüver and E.A.T. got the nod from Pepsi to do the Pavilion, Nakaya became a central person in the project. Besides handling logistics and smoothing over Japanese-American interactions, in Osaka, she designed the fog sculpture that would surround the building.Producing fog from pure water isn’t easy however. In nature, fog is often produced when the air temperature drops until the air is saturated and water droplets condense. One way to generate artificial fog would be to boil water which, when surrounded by cooler air, condenses. Another would be to dramatically cool the Pavilion's roof. Both of these approaches would require huge amounts of energy. But there was a third method, the one that Nakaya wanted to do. Fog can also be made by atomizing water i.e. basically spraying tiny droplets of water into the atmosphere.To realize her aesthetic goal, Nakaya struck up a collaboration with a physicist based in Southern California. Thomas R. Mee moved to the Pasadena area after working on a variety of weather modification projects for Cornell University in the early 1960s. After working a few years for Meteorological Research Inc.. ((This company was started in 1951 by Paul MacCready (1925-2007), a Caltech graduate who later became famous for designing and building the Gossamer Condor, a human-powered aircraft. MacCready later started another southern California company, AeroVironment, which today is one of the largest manufacturers of unmanned aerial vehicles (“drones”).)) In 1969, he started his own company. Initially, Mee Industries Inc. made niche instrumentation for weather and pollution studies. In June 1969, Nakaya contacted Mee who had never heard of E.A.T. and was unaware of plans to combine art and engineering at the Osaka fair. But he was “impressed by her knowledge of cloud physics” – Mee had met Nakaya’s father and was well-aware of snow research – and her probing questions about how one might go about making fog.Mee w agreed to meet with Nakaya and experiment with a method in which water was sprayed under high pressure through a very narrow nozzle to produce a dense cloud of tiny water droplets. More experiments and hardware development followed. A few months later, on a hot, dry August day in California, Nakaya and Mee met in his Altadena backyard, set up the equipment – 60 pin-jet nozzles connected to piping in which water was pumped at 500 psi – and successfully tested a prototype system. The result was a large cloud of artificial fog that partially obscured Mee’s house.

In June 1969, Nakaya contacted Mee who had never heard of E.A.T. and was unaware of plans to combine art and engineering at the Osaka fair. But he was “impressed by her knowledge of cloud physics” – Mee had met Nakaya’s father and was well-aware of snow research – and her probing questions about how one might go about making fog.Mee w agreed to meet with Nakaya and experiment with a method in which water was sprayed under high pressure through a very narrow nozzle to produce a dense cloud of tiny water droplets. More experiments and hardware development followed. A few months later, on a hot, dry August day in California, Nakaya and Mee met in his Altadena backyard, set up the equipment – 60 pin-jet nozzles connected to piping in which water was pumped at 500 psi – and successfully tested a prototype system. The result was a large cloud of artificial fog that partially obscured Mee’s house. The nest step was to scale up the system in Osaka for the Pavilion. Ultimately, 2,520 of Mee’s specially-crafted nozzles and 11,000 gallons of water an hour would enshroud the Pavilion in an ever-changing fog sculpture some 150 feet in diameter. The humid Osaka air cooled the air around the Pavilion so that the pure white fog that Mee’s system generated poured down over the structure in patterns that Nakaya wanted. To pull this off, Nakaya and a team of specialists carried out detailed monitoring of the environment around the Pavilion site to account for wind speed, humidity, and temperature.

The nest step was to scale up the system in Osaka for the Pavilion. Ultimately, 2,520 of Mee’s specially-crafted nozzles and 11,000 gallons of water an hour would enshroud the Pavilion in an ever-changing fog sculpture some 150 feet in diameter. The humid Osaka air cooled the air around the Pavilion so that the pure white fog that Mee’s system generated poured down over the structure in patterns that Nakaya wanted. To pull this off, Nakaya and a team of specialists carried out detailed monitoring of the environment around the Pavilion site to account for wind speed, humidity, and temperature. After Expo '70 ended, Mee's company eventually began to sell fog-making systems. A patent application he submitted in 1970 cites the possibility of using his system for agricultural purposes, either for cooling areas or frost control, as well as producing a “visible cloud” which can have a “highly decorative and entertaining effect.” By 1985, company sales were approaching $2 million. After some rough financial times as a public company, the company rebounded as Mee’s children – Tom Mee passed away in 1998 – took over the business and a controlling interest in the firm. The company saw a major expansion in 1997 when the Tennessee Valley Authority decided to install fog systems on its four dozen gas turbines to improve their efficiency. Similar orders followed and the company expanded into other areas such as providing cooling for data server installations for companies like Facebook. As of 2014, some 80 people work for the company.Fujiko Nakaya and Tom Mee maintained a working relationship, with his company providing hardware for her art installations. Since Expo '70, she has created a variety of fog works - gardens, geysers, falls - at sites around the world including the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain. Besides the "Fog Bridge" at the Exploratorium, she recently crafted an immersive environmental piece called "Veil" for the Glass House, a work of modern architecture by Philip Johnson from 1949. At the Glass House, Nakaya's fog appears every 15 minutes or so, obscuring the house (as it did with Pavilion) and making it appear to vanish.

After Expo '70 ended, Mee's company eventually began to sell fog-making systems. A patent application he submitted in 1970 cites the possibility of using his system for agricultural purposes, either for cooling areas or frost control, as well as producing a “visible cloud” which can have a “highly decorative and entertaining effect.” By 1985, company sales were approaching $2 million. After some rough financial times as a public company, the company rebounded as Mee’s children – Tom Mee passed away in 1998 – took over the business and a controlling interest in the firm. The company saw a major expansion in 1997 when the Tennessee Valley Authority decided to install fog systems on its four dozen gas turbines to improve their efficiency. Similar orders followed and the company expanded into other areas such as providing cooling for data server installations for companies like Facebook. As of 2014, some 80 people work for the company.Fujiko Nakaya and Tom Mee maintained a working relationship, with his company providing hardware for her art installations. Since Expo '70, she has created a variety of fog works - gardens, geysers, falls - at sites around the world including the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain. Besides the "Fog Bridge" at the Exploratorium, she recently crafted an immersive environmental piece called "Veil" for the Glass House, a work of modern architecture by Philip Johnson from 1949. At the Glass House, Nakaya's fog appears every 15 minutes or so, obscuring the house (as it did with Pavilion) and making it appear to vanish. As a young artist, Nakaya painted clouds. But, as she told The New York Times, the activism of the 1960s made her want to interact more directly with the environment and society. Where the elder Nakaya wanted to control and classify the creation of ice crystals, his daughter's approach is orthogonal - change, chance, and contingency dominate. Both are united, however, in combining physics with an aesthetic sensibility.

As a young artist, Nakaya painted clouds. But, as she told The New York Times, the activism of the 1960s made her want to interact more directly with the environment and society. Where the elder Nakaya wanted to control and classify the creation of ice crystals, his daughter's approach is orthogonal - change, chance, and contingency dominate. Both are united, however, in combining physics with an aesthetic sensibility.