A Boring Future

"I would sum up my fear about the future in one word: boring." J.G. Ballard; Interview (30 October 1982) in Re/Search no. 8/9

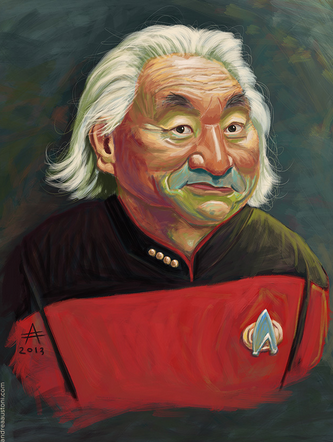

In 1962, Arthur C. Clarke postulated what became one of his "three laws" about predicting the future. In an essay titled ""Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination" he wrote: "When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong." ((from the book Profiles of the Future, 1962, revised 1973, Harper & Row))I was recently reminded of Clarke's admonition when The New York Times ran a piece called "A Scientist Predicts the Future." It was written by Michio Kaku, a theoretical physicist based at the City College of New York. Born in California in 1947, Kaku's 1972 degree was from Berkeley and his early publications dealt with quantum and string theory (his personal website says he's a co-founder of "string field theory"); the SAO/NASA database lists some 70 articles to his name. But it's as a popularizer of science that Kaku can claim the most fame.

In 1962, Arthur C. Clarke postulated what became one of his "three laws" about predicting the future. In an essay titled ""Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination" he wrote: "When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong." ((from the book Profiles of the Future, 1962, revised 1973, Harper & Row))I was recently reminded of Clarke's admonition when The New York Times ran a piece called "A Scientist Predicts the Future." It was written by Michio Kaku, a theoretical physicist based at the City College of New York. Born in California in 1947, Kaku's 1972 degree was from Berkeley and his early publications dealt with quantum and string theory (his personal website says he's a co-founder of "string field theory"); the SAO/NASA database lists some 70 articles to his name. But it's as a popularizer of science that Kaku can claim the most fame.

Besides regular appearances on the Discovery Channel, et al. Kaku has written several bestselling books on physics, especially on fantastical topics such as time travel, wormholes, and the like. A strong interest in the future and futurism runs through his work, most notably in his 2011 book Physics of the Future.

Kaku's NYT piece was essentially a reprise of his 2011 book and gave "a glimpse of what to expect in the coming decades." So far a predictions go, it's a pretty banal list: ubiquitous computing, virtual reality, brain-electronic interfaces, robots, and genetic engineering. It's the sort of list that wouldn't have been out of place back in the heyday of Omni magazine. This wasn't unexpected; a review of Kaku's book by physicist Neil Gershenfeld in Physics Today said the book described “a kind of future by committee” populated by “science-fiction staples”.

Kaku's NYT piece was essentially a reprise of his 2011 book and gave "a glimpse of what to expect in the coming decades." So far a predictions go, it's a pretty banal list: ubiquitous computing, virtual reality, brain-electronic interfaces, robots, and genetic engineering. It's the sort of list that wouldn't have been out of place back in the heyday of Omni magazine. This wasn't unexpected; a review of Kaku's book by physicist Neil Gershenfeld in Physics Today said the book described “a kind of future by committee” populated by “science-fiction staples”.

Kaku's list got some attention via social media...my favorite response to his predictions came from English sci-fi writer Tim Maughan who tweeted: "If you want to know about the future the last person to ask is a scientist. Especially a fucking physicist. Ask a banker."

There are three things worth noting about Kaku's NYT piece. First - his prognostications seem to conform to Clarke's first law. If you want to know about the future, maybe asking a sixty-something physicist isn't the way to go. Especially one engaged in a little "propheteering" that might help sell some books.

Second, Maughan's barb hits a vital spot. Interspersed among Kaku's imagined futures was his prediction that "capitalism will be perfected." This paean to the power of the free-market claimed that "the laws of supply and demand become exact, because everyone knows everything about a product, service or customer. We will know precisely where the supply curve meets the demand curve, which will make the marketplace vastly more efficient." I think this year's contradictory Nobel prizes in economics suggest otherwise. Kaku's prediction that "intellectual capitalism will replace commodity capitalism" might carry some weight in Silicon Valley but not for the 100,000s of workers actually building the stuff that makes cloud computing, etc. real and tangible.

Third, when Kaku's 2011 book - the basis for his NYT essay - came out, it was likened to the future-musings of another physicist. The Telegraph compared it to Gerard O'Neill's "deliriously technocratic vision of space exploration." Now I wouldn't go so far as to call O'Neill's future-thinking technocratic but it certainly had a fair amount of the "technological fix." But the key difference between Kaku and O'Neill lies not in their respective visions for the future but in the amount of work they put into making those futures happen.

To the first order, Kaku appears as the classic arm-waving futurist of the "we're going to have flying cars and robots and virtual sex and...and...and..." sort. O'Neill, on the other hand, actually put some labor into trying to advance his vision - and it was a very personal one at that. He got some grants to build a mass driver, he attracted students and other like-minded followers, he helped build a small community of devotees, et al..

Where other future-tellers just offer descriptive speculations, O'Neill and other visioneers deployed physical models, detailed designs, and actual calculations to develop a more rigorous foundation for imagining the future. This is why O'Neill's vision for the future - even though it didn't happen as imagined - is far more compelling and credible than Kaku's desiccated description of tomorrow.